Sensitive but unclassified: Alex Saum-Pascual on selfies, electronic literature and creativity on the Internet

Professor, artist and pioneer explores the far frontiers of self-expression in the digital age

July 27, 2016

She built a Twitter bot that breaks Jose Ortega y Gasset’s essay “The Dehumanization of Art” into 140 characters of babble and brilliance. She teaches classes with titles like “Electronic Literature: A Course on Critical Writing and Making.” She writes — if that’s actually the word for it — in Spanish and in English and something else altogether. She doesn’t seek transcendence in her poetry and seems to be sincerely ambivalent if you get it or not. If there’s muse for Alex Saum-Pascual, then that muse’s name is ephemera.

“I feel like we’re trying to preserve and categorize and explain the greatest pieces of literature and art for future generations to understand,” says the artist and UC Berkeley Spanish professor, “but I kind of just want to set fire to the museum.”

Maybe the best way to think about Saum-Pascual’s work is to picture a moving digital collage on your screen. Some elements are familiar — there are words (both Spanish and English) that are broken into lines and stanzas. Poetry says your brain. Along with the words are images and embedded videos — which is normal enough, you think. Then there are some things that are a bit stranger. Looping .gifs, audio files of a computer reading Walt Whitman’s Wikipedia entry out loud, the sounds of crashing waves, a distant singer and birds cawing overhead. Some pieces have instructions for viewing. Some require the viewer to click around the page to activate a voice. Sometimes there are errors on the page, sometimes there are broken links. Those are part of it too.

Here’s a thought experiment that might lend some clarity: “If you go to the Louvre and see the ‘Mona Lisa,’ and you come back a year later it’s going to look the same,” she says. “Of course that’s not exactly true. Subjectivity changes, circumstances change. But what if it didn’t? What if the art actually changed too, just like us? This invites revisiting, which isn’t something that you always do with traditional print literature. I don’t want to control the art — you are free to get whatever you want from it.”

If it seems like it’s difficult to describe just what exactly her art is, it’s because it is. But you can find it and should take a look. When you come back your creativity will be humming.

What language do you dream in?

To truly get a handle on her work and her point of view requires a little bit of backstory. Saum-Pascual was born and raised in Madrid. Her father is English, her mother Spanish. She was educated in Spanish schools until college and has lived in the U.S. for a decade. She is married to an American and holds a master’s from the University of Delaware and a Ph.D. from UC Riverside. Being neither here nor there seems to make her feel right at home.

“All my current work looks at the relationship between writing and other technologies,” she says. “I’m really interested in how language and how writing creatively has been changed by the use of machines. We all write with computers, but we pretend like we’re still writing without them. We pretend like they’re invisible. We don’t think about the fact that we’re using our fingers in a particular way, that when we post things online that what we’re writing is then being translated into a language we don’t understand. So I am thinking: this machine, this office mediation, is changing the way we’re writing, but is it allowing us to do certain other things too?”

The thing about Saum-Pascual’s work — both academically and artistically — is that it makes us reconsider our relationship with the Internet, and, perhaps, shows us that the boundaries of digital art are further from us than we realize.

Saum-Pascual’s interest in digital literature emerged as a response to a dynamic period in Spain right after the arrival of the new millennium. “I was interested in how [Spanish] writers were using the web to write. I started thinking through this particular situation in Spanish writing where the literary space became very constrained and institutionalized.”

What Saum-Pascual was observing was the breaking of a kind of mannered, patterned writing that had been done by Spaniards to receive funding and praise for their work, a system that was challenged by arrival of the Internet in Spain and the global economic crises of the early 2000s.

“There was an institutional instability at the time that called everything else that had been institutionalized into question,” she says. “And [with the Internet] there was this new medium that was a way to open up the cracks and see what came out. I became interested in how electronic literature filled that gap.”

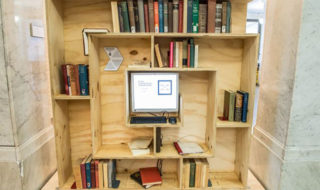

Her curiosity took shape at to UC Berkeley, where she taught classes on electronic literature. It manifested further in March 2016 when Saum-Pascual, along with the Berkeley Center for New Media and the Doe Library, curated the exhibit No Legacy, a collection of Iberian digital literature that was presented alongside print works of the 20th-century avant-garde that is currently being displayed in the Bernice Layne Brown Gallery in Berkeley’s Doe Library. Despite her engagement with the theory of electronic literature, Saum-Pascual sought a deeper understanding.

“I was teaching those classes and trying to understand what this new writing was, but I didn’t have the words,” she says. “Because [digital literature] isn’t a visual culture, and it isn’t a literary culture either, I didn’t really have a scholarly tradition to draw from, so when I was doing more research I felt like there was a serious lack. I couldn’t express it. I didn’t really want to write an essay describing things, and I felt that digital literature was something else, something different. I had a sense – an intuition— that it had something to do with the making, that there was something about making literature a performance … I thought this has to be it.”

‘We are obsessed with our faces’

“I’m interested in ephemerality,” she says. She is talking about her art, particularly two series of recent creations titled #SELFIEPOERTY: Fake Art Histories & the Inscription of the Digital Self and #SELFIEPOETRY: WOMEN & CAPITALISM, before pausing and expounding.

“I do not seek transcendence in my art. I do not need perfection. There’s a preciousness of the digital. It’s always there and it’s never there,” she says referencing the cloud, maybe, or the shelf life of items posted online, or something else entirely.

Ducking transcendence, or at least the pursuit of it, seems like a good thing too, because her work — by its very nature — is somewhat fragile. The supports that hold her pieces upright rely on external plug-ins or materials hosted on different sites that have been incorporated into the work. Pages are heavy, load times lag, and not all browsers support the files that exist in the piece. Mobile viewing is either impossible or yields an altogether different product. The poetry is alive, and, like every other living thing, it can also die.

Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“I love the precarious nature of it,” she says. “I think it’s very precious. A piece could be displayed at a gallery and it might not work. There’s a preciousness to the digital.”

What is alive, at least for now, are 17 pieces that were created in a digital workshop called newhive.com. They look at things like “the untruth behind our artistic or literary histories,” and “how the self can be reinterpreted against a vague and unorthodox selection of artistic and literary movements,” and “personal matters,” which is a bit of an understatement. All of the pieces feature something personal of hers — a spinning image of her passport photo, her voice, 10 identical videos of her looking around the screen before speaking directly to the viewer.

“When you’re looking at yourself in the mirror, it is a very private experience,” she says. “But when you are creating a digital reproduction for other people to see, it’s a different, public performance of a face. It becomes a kind of avatar that becomes your mask in the world for others. You’re controlling it [your avatar], even though it’s something that the world already knows about you. It’s very aestheticized and was something I tried to challenge.”

Her challenges are finding homes. Her work was exhibited in code/switch at the Woman Made Gallery in Chicago this summer, and her piece 24/7 was a finalist at the Print Screen Festival in Israel in June.

A future of creative joy

Asking Saum-Pascual what the future looks like is a lot like asking an explorer what’s beyond the edge of a map — you get the sense that almost anything could be out there. This is doubly true when you keep in mind that she is someone who took a concern about her home country’s digital inheritance and grew it into a kaleidoscopic collage of poetry, sound, and image that is capable of calling the relationship between people, art and the Internet into question.

“[#SELFIEPOETRY: WOMEN & CAPITALISM] was a result of almost a decade of living in the U.S. and the use of social media,” she writes on her website. “This series is in progress, will never be complete, and will constantly change.”

And so the creation continues for Saum-Pascual, who finally feels like she has the medium she needs to make her art. She embraces the hiccups in programs (“what if these glitches are rhetorical questions or challenges to what I was intending to do?”), she gets lost in noises that splash around on her digital canvas (“I find it beautiful. There’s something in getting lost in the that repetition of sound — it’s a poetic experience for me. I get mesmerized.”) and she continues to encourage her students to explore (“about a third of my students in the Digital Humanities pilot course completed their finished their final projects on newhive.”)

There’s also book of short stories in her future, a collaboration with a computer programmer at Stanford. And while they plan on publishing it through conventional methods, they’re incorporating an algorithm he built that understands semantic content, allowing it “read” through huge collections of data and then “understand” what people meant or implied. The pair plan on feeding the algorithm journals and exploring the voices that come out the on the other side.

At the heart of all of these creations is joy.

“I’m really just enjoying myself,” she says. “I’ve the lost the fear of creating and now I have so much joy doing this. I love the process of making. I love it.”