Marian Diamond, known for studies of Einstein’s brain, dies at 90

A pioneering neuroscientist, Diamond provided the first evidence that the brain's anatomy changes with experience, establishing the value of mental enrichment throughout life

July 28, 2017

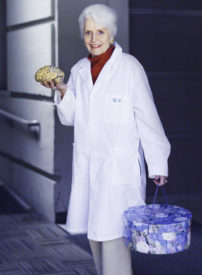

Marian Cleeves Diamond with a preserved human brain. Elena Zhukova photos (2010).

Marian Cleeves Diamond, one of the founders of modern neuroscience who was the first to show that the brain can change with experience and improve with enrichment, and who discovered evidence of this in the brain of Albert Einstein, died July 25 at the age of 90 at her home in Oakland.

A professor emerita of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley, Diamond achieved celebrity in 1984 when she examined preserved slices of Einstein’s brain, finding that he had more support cells in the brain than average.

Her main claim to fame, however, came from work on rats, in which she showed that an enriched environment — toys and companions — changed the anatomy of the brain. The implication was that the brains of all animals, including humans, benefit from an enriched environment, and that impoverished environments can lower the capacity to learn.

Diamond was awed that a small, three-pound mass of protoplasm like the brain was the most complex structure known to humankind.

“Her research demonstrated the impact of enrichment on brain development — a simple but powerful new understanding that has literally changed the world, from how we think about ourselves to how we raise our children,” said UC Berkeley colleague George Brooks, a professor of integrative biology. “Dr. Diamond showed anatomically, for the first time, what we now call plasticity of the brain. In doing so she shattered the old paradigm of understanding the brain as a static and unchangeable entity that simply degenerated as we age. ”

Her results were initially resisted by some neuroscientists. At one meeting, she later recalled, a man stood up after her talk and said loudly, “Young lady, that brain cannot change!”

“It was an uphill battle for women scientists then — even more than now — and people at scientific conferences are often terribly critical,” she wrote in her 1998 book, Magic Trees of the Mind: How to Nurture your Child’s Intelligence, Creativity, and Healthy Emotions from Birth through Adolescence, co-authored with Janet Hopson. “But I felt good about the work, and I simply replied, ‘I’m sorry, sir, but we have the initial experiment and the replication experiment that shows it can.'”

She subsequently demonstrated that the brain can continue to develop at any age, emphasizing the importance of growth and learning throughout life, that male and female brains are structured differently and that stimulating the brain even enhances our immune system.

Join the conversation on UC Berkeley’s Facebook page.

Diamond was not only a pioneer in neuroscience and anatomical and behavioral research, but a beloved teacher and mentor who was dedicated to university and public service. For decades she could be seen walking through campus to her anatomy class carrying a flowered hat box containing a preserved human brain.

In her typically packed classes, she would gently lift the brain from its wrapping and express her awe that such a small, three-pound mass of protoplasm was the most complex structure known to humankind.

One of those students was Wendy Suzuki, who said in a 2011 TEDx talk that the day she first saw Diamond unveil the brain was “the day I wanted to become a neuroscientist.” Suzuki is now a neuroscientist at New York University and author of the 2015 book Healthy Brain, Happy Life: A Personal Program to Activate Your Brain and Do Everything Better.

Diamond’s anatomy lectures remain on YouTube to inspire another generation: One has received more than 1 million views over 10 years.

Worldwide, Diamond’s ideas fortified efforts of physicians and educators in promoting early nurturing and educational enrichment of children. Her scholarship and personal efforts led to the building and management of orphanages, including one in Cambodia, where she worked to enrich the minds of impoverished children. Her work on environmental enrichment has been so widely accepted that it even led to significant improvements in laboratory and zoo animal care, said Daniela Kaufer, a UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology.

She took every opportunity to encourage activities, both mental and physical, that enrich the brain, and she herself continued to conduct research and teach until 2014, when she retired at the age of 87.

Her life was memorialized in the 2016 documentary film My Love Affair with the Brain: The Life and Science of Dr. Marian Diamond, by Catherine Ryan and Gary Weimberg.

Among her last words were, “If you’re going to live life, you’ve got to be all in.”

Growing up in an enriched environment

Marian Cleeves was born Nov. 11, 1926, in Glendale, California, the youngest of six children of Dr. Montague Cleeves, an immigrant from northern England, and Rosa Marian Wamphler, a UC Berkeley graduate who abandoned her Ph.D. studies to raise her children in La Crescenta. Like her siblings, Marian attended La Crescenta grammar school, Clark Junior High and Glendale High School. She enrolled in Glendale Community College before transferring to UC Berkeley in 1946, where she played and lettered in tennis. Her interest in in sports and exercise continued into her 80s as Diamond swam daily on the Berkeley campus before turning to teaching and laboratory activities.

After obtaining a bachelor’s degree in 1948, she continued her studies at UC Berkeley as the first female graduate student in the Department of Anatomy. Her doctoral dissertation thesis, “Functional Interrelationships of the Hypothalamus and the Neurohypophysis,” was published in 1953. While working on her Ph.D., Diamond also began to teach, developing a lifelong passion.

After working as a research assistant at Harvard University (1952-53), Diamond was appointed the first woman science instructor at Cornell University (1955-58), where she taught human biology and comparative anatomy. She subsequently moved west to teach anatomy to medical students at UC San Francisco.

She returned to UC Berkeley in 1960 as a lecturer, continuing her studies of brain anatomy. By 1964, Diamond had the first actual evidence — actual anatomical measurements — “showing the plasticity of the anatomy of the mammalian cerebral cortex.”

Her aptitude as a teacher and her revolutionary research findings led to her appointment in 1965 as an assistant professor of anatomy — a department since rolled into the Department of Integrative Biology — and later elevation to full professor. She subsequently served as the assistant and associate dean of the College of Letters and Science and director of the Lawrence Hall of Science from 1990 to 1996, where she was able to use her findings on enriched environments to develop educational programs in science and mathematics for students in preschool through high school.

In seminal studies during the 1960s, Diamond demonstrated that enriched environments like this rat cage with toys and companions enhance learning. Marian Diamond photo, 1964.

Brooks said that several landmark publications by Diamond shaped the field of neuroplasticity. In a 1964 paper, Diamond first showed that the structure of the cerebral cortex of young animals could change in response to environmental input. In a 1983 paper, she first showed sexual dimorphism, that is, differences between male and female animals in the structure of the cerebral cortex of young and old animals.

In a 1985 paper, she first showed that the structure of the cerebral cortex of older animals could change in response to environmental input, and influenced learning capacity.

“Her seminal work on environmental enrichment and neural plasticity spawned an entirely new field in modern neuroscience,” said neuroscientist Robert Knight, a UC Berkeley professor of psychology.

Along the way, in 1984 Diamond received four blocks of the preserved brain of Albert Einstein; the work on Einstein’s brain was to make her a media celebrity. By comparing results with previous analyses on control brains, the Diamond lab learned that the frontal cortex had more non-neuronal, or glial cells, per neuron than the parietal cortex. After many years of research, Diamond and her team discovered that the big difference in all four areas was in glial cells: Einstein had more glial cells per neuron in the inferior parietal area than the average male brains of the control group. This seminal work put a spotlight on this understudied cellular population and paved the way to a new area of neuroscience study — glial biology.

In a career at UC Berkeley spanning half a century, Diamond inspired thousands of students over generations. In her course Integrative Biology 131 (IB131, Human Anatomy), Diamond annually filled Wheeler Auditorium with her stunning lectures.

Another of her innovative courses was the Anatomy Enrichment Program, which for more than three decades functioned as both a teaching opportunity and an outreach effort to elementary school children in Berkeley and Albany. The spring 2017 semester marked the 40th year of anatomy students teaching elementary school children.

“Marian Diamond (will be) remembered as an esteemed colleague, a friend and a gentle soul who by nature and nurture sought to extend happiness and accomplishment to her students, colleagues and others,” Brooks said.

Diamond was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a California Professor of the Year and National Gold Medalist from the Council for Advancement & Support of Education, a UC Berkeley Alumna of the Year, recipient of the 2012 Clark Kerr Award for Distinguished Leadership in Higher Education and a 1975 Distinguished Teaching Award recipient from UC Berkeley.

She also authored the book Enriching Heredity: The Impact of the Environment on the Anatomy of the Brain (1988) and co-authored The Human Brain Coloring Book (1985).

Diamond was preceded in death by her husband of 35 years, Arnold (“Arne”) Scheibel, who passed away April 3. She is survived by Catherine Theresa Diamond of Taipei, Taiwan, Richard Cleeves Diamond and Jeff Barja Diamond of Berkeley, and Ann Diamond of Mazama, Washington, all children of her first marriage to the late Richard M. Diamond.