In campus records 49 years and still loving it

When assistant registrar Karen Denton started working at Berkeley at 20, she had one job: to remove incompletes. Now, at 71, she has more responsibilities than she can count and no plans to retire.

March 4, 2019

When Karen Denton got a job in UC Berkeley’s registrar’s office at 20, she had one job: to remove incompletes. “I did that all day every day,” she says. Her tools of the trade? A fountain pen, an inkwell, an eraser, a razor blade and a marble. At 71, Karen has been the assistant registrar for two decades and has worked in records for 49 years. And she has no plans to retire anytime soon. “Why would I retire?” she asks. “I love working here. I love the students. I love the challenge.” But she will leave sometime, and before she does, she wants to have all student records — dating back to the late 1800s — digitized.

Karen Denton has worked in the registrar’s office at UC Berkeley for 49 years. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Following is a written version of Fiat Vox episode #50: “In campus records 49 years and still loving it.”

When Karen Denton began working in the registrar’s office at UC Berkeley more than 50 years ago, she had one job.

“When I first came, I did “I” removals. You did that one job all day long.”

[Music: “The Poplar Grove” by Blue Dot Sessions]

It’s not what it sounds like. She wasn’t doing surgery. She was removing incompletes from student records, changing the “I” on the record to a grade. And although it wasn’t a medical procedure, it did require attention to detail and a lot of patience.

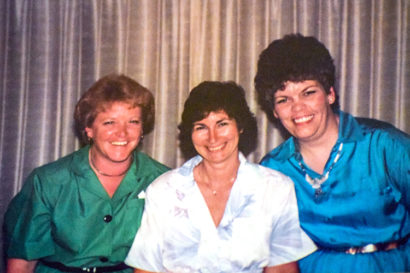

Karen Denton was first hired to work in UC Berkeley’s registrar’s office in 1967 when she was 20. (Photo courtesy of Karen Denton)

“For my first one or two weeks, you had to learn how to print. Everybody had to write the exact same way because we would write on students’ records. So, any changes that we made to a record, we would handwrite them with a fountain pen in black ink. Your tools of the trade were a fountain pen, an inkwell, an eraser, a razor blade and a marble.”

So, if she made a mistake on a record, she would erase it, then use the razor blade to carefully get the rest of the ink off, then use the marble to smooth down the paper, so she could write on it again. Otherwise, the ink spread.

[This is Fiat Vox. I’m Anne Brice.]

It was June 1967. Karen was 20 at the time. She’d just received her associate’s degree at Contra Costa Community College on Friday and started her new job at Berkeley the following Monday.

“Was it easier to get jobs back then?” I ask.

When Karen was first hired, she had one job: To remove incompletes on students’ records. Her tools of the trade? A fountain pen, an eraser, a razor blade and a marble. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

“Oh definitely, definitely,” says Karen. “Women would get pregnant and you were not secured of having your job when you came back. So, there were always openings. It was very easy to get in here.”

Things were also more structured and restrictive. Karen worked with at least 20 other women in records, and every day they would take breaks and have lunch at the exact same time. If someone was late getting back, they’d hear about it from their supervisor.

“I did that a few times,” she says. “Didn’t take me much to learn to never do that again. You were in trouble.”

[Music: “Picnic March” by Blue Dot Sessions]

And each of them had one main, often menial responsibility that they would do all day long.

When it was final grade processing time, they would go down to the basement of Sproul and put labels on 25,000 students’ records. Then, they would add up all of the credits for each student on each record card.

“So, I mean, basically you’re supposed to be working and being quiet. And then somebody would say something, and you’d start laughing because it was very, very tedious work. And, Mrs. Leidy would come down and she would just look at you,” she laughs.

If they found an error on the units and grade points line on the record card, they couldn’t use their trusty razor blade-marble technique. Instead, they would send the corrections to key punch and it would also go to Carolyn Teet, who would amend the record with the special Berkeley font typewriter ball.

In the late 1960s, Carolyn Teet in the registrar’s office would lock up the Berkeley font typeball every night. (Photo by Dominika Komender via Wikimedia)

Although I have used a manual typewriter — my parents had an old one when I was a kid — I didn’t realize that by the 1960s, there were these electric typewriters that used rotating typeballs. That’s what the registrar’s office had.

Every night, Carolyn Teet would lock up this ball.

If a student got their hands on the ball, they could change their own grades or other students’ grades. That’s a lot of power.

“We had one person who had changes made to their transcript. I’m not quite sure who did this, but it was the boyfriend of somebody that worked in the office, and they added a term that was actually from somebody else’s record. I actually found the record that it came from.”

Today, things in the registrar’s office are different.

With 49 years of service at UC Berkeley, Karen isn’t slowing down. “Why would I retire?” she asks. “I love working here.”

Karen, who has been the assistant registrar for the past two decades, has more responsibilities than she can count. She does all the grade processing, and her expertise helped to provide enhancements when Berkeley was implementing Campus Solutions, a UC-wide information system where students go to access everything from application and financial aid status to grades and transcripts.

But, Karen says, it’s still important that others know how things were done.

[Music: “Slimheart” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Well, you know, the thing about it… yes, we’re in a new system, but if you don’t understand the old system, you can’t work in the new system. You have to understand why we did things the way we did. So, the people who are here right now have been in the old system. We talk every day. You have to transfer the knowledge.”

Gia White (left), an administrative director for the Institute of European Studies, worked with Karen in the Records Division over 30 years ago as a work study student. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

At 71, Karen has worked in the registrar’s office at Berkeley for 49 years. (She was gone for a little while after she got married and moved to Hawaii when she 23. She came back two years later.)

We couldn’t find out if she’s the longest employee at UC Berkeley, but she’s definitely up there as one of the longest. She says she doesn’t have any immediate plans to retire, a question people always ask her.

“I love working here. I love the students. I love the challenge. I feel that I’ve had a big part in making changes to Campus Solutions.”

But she will retire someday, and before she does, she wants to have had all the student records digitized. Some of the early ones are already done, thanks to Karen, but there are still boxes and boxes of transcripts stored off-site that only exist on paper.

It’s a big task, but if someone has the patience and dedication to make it happen, it’s Karen Denton.

Before she retires, Karen says she wants to have had all student records digitized. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

This profile is part of a series highlighting staff who have worked at UC Berkeley for 30 years or more, as a way to celebrate their contributions to the campus. It’s produced by Anne Brice and Gia White, an administrative director for the Institute of European Studies, who has worked at Berkeley for 30 years.

Related stories: