D-Day anniversary evokes strong, 75-year-old memories for Berkeley faculty

For three Berkeley emeriti, D-Day remains a piece of living history

June 5, 2019

American assault troops gather on Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives)

For most of us, D-Day is just another date in history.

Tomorrow marks 75 years since 156,000 troops, most of them American, British and Canadian, engaged in a sea and air armada during World War II that, on June 6, 1944, successfully broke Nazi Germany’s hold on Western Europe.

The enormity of the day was immediately evident to some; for others, time would be needed to process the meaning.

For three UC Berkeley emeriti, D-Day remains a day unlike any other.

Here are their stories.

Karl Pister, professor emeritus of engineering

“I was 18. I was living in Berkeley at the International House, which was then called Callaghan Hall, as a student and an enlisted Navy man. I was part of the V-12 program designed to produce naval officers.

“I enlisted on Dec. 7, 1942 and was sworn in at the old Cowell Hospital (Berkeley’s student health care center from 1930-1993). I was an engineer, going to school year-around. I got my degree in two years and eight months from the time I started Cal in 1942.

Karl Pister was 18 and in uniform in Berkeley when he heard of the invasion of Normandy.

“Callaghan Hall was given over to the Navy, the Marine Corps and the Naval ROTC. There were something like 1,000 of us on campus, and most lived in Callaghan Hall or in fraternities, which were mostly empty because of the war.

“When we got the news of D-Day, we got it through newspapers. There were a lot of them around, not like today. But, also not like today, we had to wait to learn what was happening.

“It was clear to us that there was a switch in the war. Now, for us, the war in Europe was going to wind down faster than the war against Japan, because of the vastness of the Pacific Ocean and all the islands Japan had acquired. Obviously, in looking back on it, we had very little understanding about how much was left to do in Europe.

“We didn’t have any organized party or anything after getting the news. We did have some smaller celebrations, mostly guys getting together on the weekend. (D-Day was a Tuesday), and there was no time for us to do anything during the week. We were totally regimented, going from getting up at 6 a.m. until going to bed at 10 p.m.

American troops get ready to hit the water off the coast of Normandy as their landing craft closes in on Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. (Photo courtesy U.S. Army)

“I graduated from Berkeley in June of 1945. I went to Okinawa just after the war was over. Japan was beaten, but there were still Japanese who didn’t want to acknowledge that and hid in caves.

Although, when I graduated, I thought I had enough education. A year of service in a Naval Construction Battalion changed my mind. I returned to Berkeley for an M.S. in civil engineering and then a Ph.D. in theoretical and applied mechanics at the University of Illinois. I was then fortunate to gain a faculty appointment in civil engineering at Berkeley in 1952. I remained active in the Naval Reserve and retired in 1969 as a captain in the Civil Engineer Corps. I retired from UC Berkeley in 1996.

Louise George Clubb, professor emeritus of Italian studies and comparative literature

“We were living in San Antonio, and my father (Alexander George) was in England with the 29th Infantry Division, but that is all we knew at the time. It was all very hush-hush. We knew he was training troops, but we didn’t know much more than that.

“Even when we received the news about D-Day, we didn’t know he was involved until it was announced that his regiment, the 175th, had taken part in the invasion at Omaha Beach.

“I just remember hearing the reports on the radio first. Then we got the newspapers. We learned things a bit at a time.

The report of the D-Day invasion led to Berkeley students gathering together, as the Berkeley Gazette reported.

“One of my mother’s main sources of news was the West Pointers’ network. Army wives were always communicating with each other, exchanging information.The wife of the commander of the 29th Division was always in touch with her husband and we heard from her a lot.

“We lived in a state of great tension throughout the war years. We were not being bombed like European countries, but we were all keyed up. We were never far from the war. There was rationing of almost everything — food, gas. The war monopolized public attention on all levels. The trains were always extremely packed, and it was hard to find housing.”

Richard Buxbaum, professor emeritus of international law

“I was 14 and following the war very closely. Finding out what was going on was very important to us all. It was mostly concern for our families. We knew my father’s brother, Martin, was in (Gen. George S.) Patton (Jr.’s) 4th Armored Division.

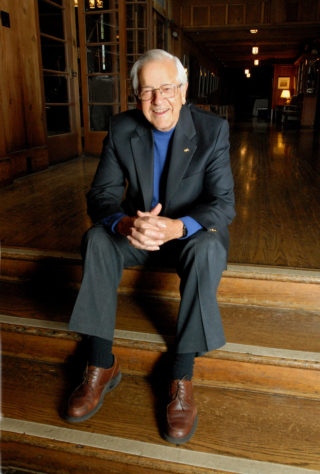

Richard Buxbaum

“There was some inevitability about an invasion, and we debated when it would be, while there was fighting in North Africa and then in Sicily. It was all a question about what would be the quickest way to move toward the expected victory. We were optimistic and, at the same time, we of the émigré generation were concerned about those who had been left behind. The quickest way was very important to us.

“In that context, we wanted to know where the 4th Armored Division was, as part of the invasion.

“When D-Day happened, it was all over the newspapers in 96-point headline type on June 7. No one talked about anything else. We had almost sunk the British Isles with the weight of our troops massed there. It was the burning issue of the time. We had all been waiting for the hammer to fall, and now it had.

“It seemed momentous, that this was the beginning of the end. The fact that it took another 11 months, people were surprised.”