Scientific glassblower continues century-old campus tradition

Jim Breen, in the College of Chemistry Glass Shop, is one of only about 50 university glassblowers left in the U.S.

June 10, 2019

To find Room B63 in the nondescript, industrial basement of UC Berkeley’s Hildebrand Hall, it’s best to follow your ears. On a recent afternoon, the Troggs’ 1966 rock hit “Wild Thing” led the way. But once inside the door, don’t expect a party, despite the non-stop music and abundant glassware.

This is the College of Chemistry’s Glass Shop, the busy workspace of scientific glassblower Jim Breen. For the past 16 years, the highly-skilled artisan has created glass apparatus and other vessels for Berkeley researchers — not just those in chemistry, but in engineering, earth and planetary science, physics and other fields.

The 750-square-foot shop is crowded with the tools of Breen’s trade — gas torches, three glass lathes, blow tubes, tweezers, shears, calipers, glass rods and t-valves, break-resistant eyewear and gloves. There’s also a large oven, to heat-treat the glass, which can reach 1040 F, and torches that burn even hotter, up to 3,000 F.

Two decades ago, three glassblowers staffed Berkeley’s shop. But today, Breen, 66, works solo. His customers are constant: Sometimes every 15 minutes, Ph.D. students and postdoctoral fellows pop in for repair of a cracked glass gadget or to tap Breen’s design expertise.

“With our researchers, it’s pedal to the metal. They’re under pressure and have to put out research papers,” says Breen, who typically has a 150-to-200-hour backlog of jobs. “They need an apparatus, and the project can’t start until I finish it. You get good at tap dancing.”

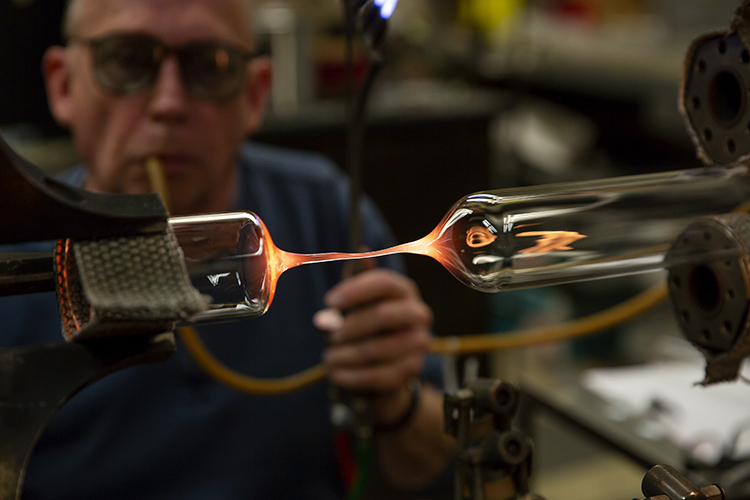

“Blowing” glass refers to the process glassblowers use to keep the liquid, molten glass they’re working with from collapsing. They puff air through a long rubber tube and into the glass piece as it’s being held, rotated and fashioned on a lathe.

A tube of glass is separated by glassblower Jim Breen, and a test tube bottom is created on the piece on the right-hand side. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Breen, who’s blown glass for about 40 years, is one of a dwindling number of scientific glassblowers in the United States. Fifty years ago, the American Scientific Glassblowers Society had roughly 1,000 members; for the past 25 years, the number’s circled 500. But Breen says only about 50 work at colleges or universities.

It’s been more than 20 years since Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory had a glassblower, for example, and none remain at UCLA. At UC Riverside, three glassblowers have dropped to one, who just works Wednesdays. Budget cuts in higher education, mail order glass equipment and new research methods help explain the decline.

Alex Shtromberg, College of Chemistry assistant dean of engineering and facilities, says that, so far, Berkeley’s bucked the trend to close shop. The college has had a glassblower for more than 100 years — since about 1917, when the first, William J. Cummings, arrived at Berkeley from an East Coast light bulb factory, where he’d learned his trade blowing light bulbs.

“Jim’s profession is unique, and it’s a small niche not every university has,” says Shtromberg. “I wouldn’t say scientific glassblowing is a dying trade, but it’s the one universities aren’t always keeping under their roofs.

“When previous glassblowers have retired at Berkeley, there was always a discussion — Do we need the shop? But the faculty were very strong on keeping it open. Jim’s value is that he can provide immediate help, right here. He can repair glass set-ups in place and guide graduate students, who sometimes don’t know exactly what their needs are. We’re lucky in that way.”

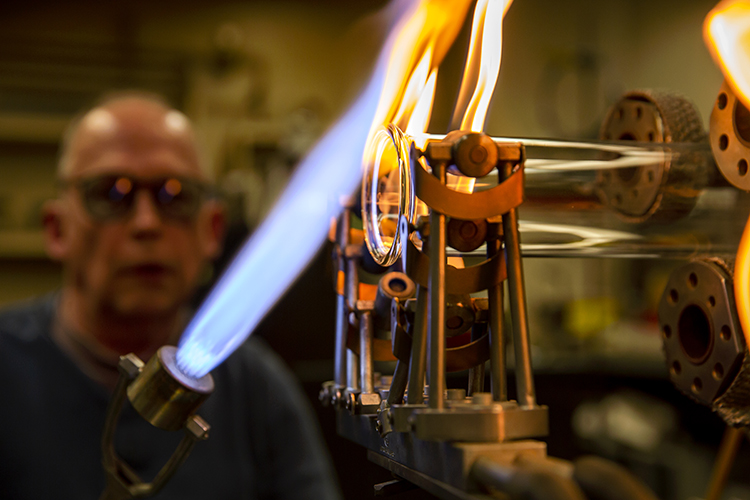

Jim Breen flares the end of a glass tube and makes a shock-resistant edge. He won the large hand torch in a glassblowers’ raffle in Grass Valley. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Glassblowing in his DNA

Breen’s passion for glass began in Oakland in the late 1960s, when he took his mom’s advice in high school and learned to make stained glass at a local recreation center.

“She told me, ‘It’s a lost art. You need to check it out,’” he says. “She’d also analyzed my nature and knew I was mechanical and artistic. I was good at making stuff. All of us (in the family) were. But I was a little more patient and adept at detail.”

After high school, Breen kept stained glass as a hobby, but chose a job in Alameda at a glass shop in the semiconductor industry. There, he worked with quartz glass to make high-temperature carriers for silicon chips. Later, in the early 1980s, he created neon signs, mastering the skill of bending glass tubes, and spent 10 years in San Francisco at a neon shop he described as “bohemian.”

“It was very hip, at the time,” he says of neon. “I loved the manipulation of glass. Ever see Fog City Diner’s sign? We did that.”

Breen also added to his resumé a job making laboratory glassware in Hayward and another in Fremont, where he crafted lasers of glass and ceramic for light shows and medical uses.

Glassblower Jim Breen sits at the glass lathe in the College of Chemistry Glass Shop in Hildebrand Hall. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

It was Breen’s father, a chemical analyst at Shell oil company, who Breen says inspired him to become a laboratory glassblower. “At the dinner table,” says Breen, “Dad would impart his knowledge of chemistry, of science, to his four sons. He’d also tried his hand at glassblowing.”

When Breen was in his early 30s, aspiring to a glassblowing job at a university or a national laboratory, his father, impressed with a large glass bell jar his son had made, presented Breen with a swivel — a small device that connects a glassblower’s blow hose to a piece of glass.

“It was subtle, but that made it clear he had confidence in me. His approval gave me the impetus to keep going,” says Breen. Later, he learned that his distant ancestry includes a glassblower and a chemist — proof, he says, that “glassblowing is indeed in my DNA.”

Breen’s dream job materialized in 2002 at Berkeley. Campus glassblower Tom Lawhead, who’d held the job for 18 years, retired, and a faculty/staff task force assembled by the College of Chemistry’s dean chose to keep the shop open.

Using a carbon paddle, Jim Breen seals together a glass cold trap and adds a flange, or rim. Woven, heat-resistant glass tape keeps the pieces secured. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Technical skills aren’t enough

What makes a good glassblower? Bob Ponton, president emeritus in New York of the American Scientific Glassblowers Society, says it’s more than being “an adept technician.”

“You need to be a people person,” he says, “and able to deal with scientists from all backgrounds, countries and language levels, and to sit there calmly and help them. You want them to succeed, because then you succeed. You have to love to solve problems.”

Also required is “the ability to communicate, and to communicate well,” adds veteran scientific glassblower Joe Walas, who’s worked at several East Coast universities. “Frequently, researchers have an idea of what they want, but they’re not able to express it verbally or on paper.”

Breen, who enjoys collaborating with researchers, welcomes them to what he jokingly calls his “altar of ideas” — a tabletop in his shop where he patiently listens to their plans, looks at their sketches — or helps them make a few — and even interprets their hand gestures to determine the right custom glass apparatus for their experiments.

“A lot of the time, it’s just in their imagination, and we come up with a design. If they don’t speak English well, we point, look at catalogs. I have to be clairvoyant, at times, to understand,” says Breen. The relationship scientists build with on-site glassblowers is an important tool in their research, he says, and not available at most schools.

And if a piece he’s made for them breaks, “I don’t judge them,” says Breen. “They’re always mortified, particularly first-year students. I tell them, ‘If you’re not breaking glassware, you’re not working hard enough.'”

Associate professor Daniel Stolper (right) and postdoctoral researcher Max Lloyd talk with glassblower Jim Breen about a new project for their lab in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Stable isotope geochemist Max Lloyd brought Breen pipe cleaners twisted into various shapes to simulate the five specialized glass pieces he needed for his climate change work. The finished tubes would snap onto an enormous glass chemistry apparatus — a so-called Schlenk, or vacuum, line — that Breen has built and installed in the lab of Daniel Stolper, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science.

“It’s my impression that Jim’s eyes lit up when I told him what I needed,” says Lloyd, “and that I was going to do chemical workups with fossil wood from a meta-sequoia tree that was 50 million years old” to better understand the temperature and climate in which trees grow.

Lloyd, a postdoctoral researcher, says he’s grateful Breen “understands science. Without him, we’d have to order custom pieces from someone we’d never talked to and likely send them back for alterations. That’s a terrifying way and unproductive way to work.”

Breen says it’s especially rewarding for him to help young scientists aspiring to publish their work and become professors.

A favorite project was a jet-stirred reactor he built about seven years ago for a postdoctoral fellow — with help from other campus shops — to study the combustion of molecules. She was struggling, in part, because “men were discounting her,” says Breen. “But I had faith in her. And based on this work, she got a professorship in Florida, a tenured job.”

Jim Breen says his favorite part of the job is “the human interaction,” the chance to collaborate with researchers and help them decide what custom equipment they need for their experiments, and then to build it for them. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

‘Routine isn’t what Jim does’

Controlled atmosphere “gloveboxes,” or “dry boxes” — sealed containers that allow researchers to manipulate air- and water-sensitive materials using gloves built into the boxes’ sides — are causing a drop in wet chemistry, which is scientists’ use of classical methods and laboratory glassware to test materials in liquid form.

“The glass you use inside these boxes is cheaper and simpler to use, and vacuum lines are less common in labs now,” adds John Arnold, a Berkeley chemistry professor. “Also, mass production of fully-assembled glass equipment has increased in places cheaper than California. You can send them drawings and get a quote.”

But Arnold, who learned glassblowing as a teen in community college in England, adds that “much of what these commercial glass shops are doing is routine, repetitive work. Routine isn’t what Jim does.”

When researchers visit the College of Chemistry Glass Shop, their projects are often “in their imagination,” says Jim Breen, “and we come up with a design.” They grab a stool at a tabletop he calls his “altar of ideas.” (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Berkeley juniors and seniors in Chemistry 108 — an inorganic synthesis lab that teaches them synthetic chemistry research skills — are taught glassblowing techniques, but they are basic ones, such as how to seal up a sample in a glass tube. Repairing glassware they crack or designing complex vessels for experiments aren’t in the syllabus.

That’s why Breen’s in business. And he’s not ready to retire yet. He does wonder, though, if he’ll be replaced when that day arrives. “This work will always be needed,” he says.

As an experimental chemist, says Arnold, “it would be a sad day for me and my group if we didn’t have someone like Jim to talk to.

“It’s a shame that manual skills like this, with your hands, are becoming less and less important. It’s easy to imagine that this work grows on trees — that if you break something, you can just buy more. But it’s been made with a skill people have worked on and taken the trouble and pride to develop. That still has huge value and can’t become lost.”