Coronavirus: Fear of Asians rooted in long American history of prejudicial policies

For 30 years, hundreds of thousands of Chinese and Japanese immigrants were detained on Angel Island before being deported or allowed into the country

February 12, 2020

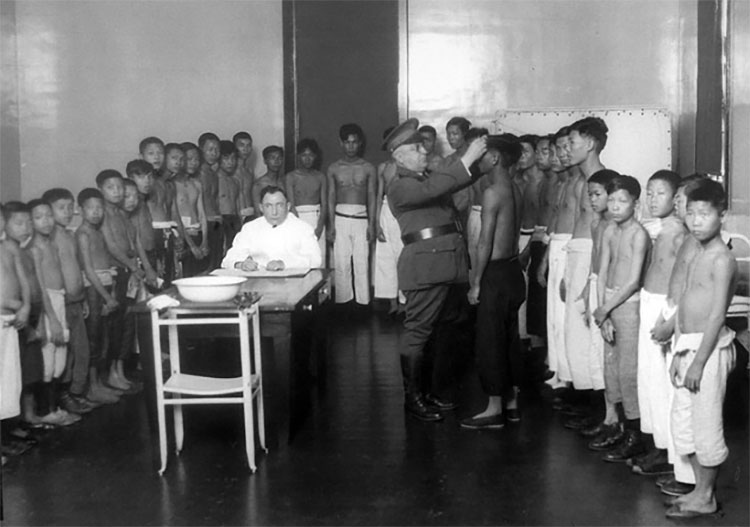

A group of Asian immigrants are given exams by medical staff at Angel Island Immigration Station in the early 20th century. The tests were often invasive and given without patient consent. (Photo courtesy of Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation)

As the number of novel coronavirus cases rises, anxiety over the potentially deadly disease has been partly based on something other than health concerns. From denigrating social media memes and GIFs to incidents of outright prejudice around the world, many Chinese people, and people of Asian descent perceived to be Chinese, are being avoided and blamed for spreading the pneumonia-causing virus, which originated in Wuhan, China.

This anti-Asian xenophobia has a history rooted in decades of discriminatory and biased American public health and immigration policies that have targeted, and continue to target, immigrants from Asia because of the perceived threats they pose to America’s dominance domestically and abroad, according to two UC Berkeley experts who have studied the history of race in America.

“There’s a part of that original history of xenophobia and racism in America from the 19th and 20th centuries that is coming back,” said Winston Tseng, a Berkeley research scientist and lecturer in the School of Public Health and in Asian American and Asian Diasporas Studies. “History is resurfacing again, with China becoming a stronger country and more competitive and a threat to U.S. dominance today, just like Japan was a threat in the second world war.”

Resurfacing history

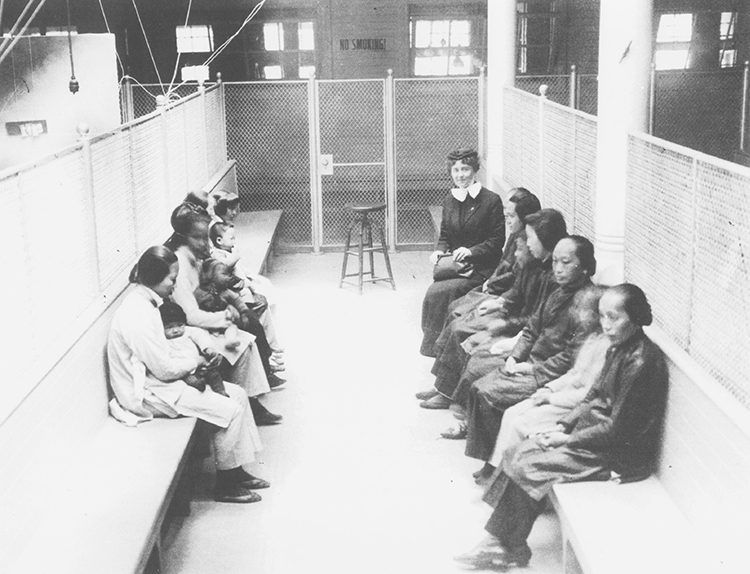

Asian immigrants signing documents upon arriving at Angel Island Immigration Station. The facility’s staff often could not understand what immigrant families were trying to say in their native language, which led to misunderstandings. (Photo courtesy of National Archives)

Tseng pointed to the immigration station at Angel Island where, between 1910 and 1940, over 225,000 Chinese and Japanese immigrants were detained under oppressive conditions for as long as six months.

This federal facility monitored the flow of Chinese immigrants entering the country after the implementation of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prevented Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States.

For more than 15 years, Winston Tseng has been a research sociologist and lecturer at UC Berkeley. (UC Berkeley photo)

It was the first immigration law that excluded an entire ethnic group.

Many of the immigrants were quarantined and given invasive medical examinations and interrogations at the facility without their consent or actual evidence of disease. Public health authorities, in turn, misrepresented Asians as diseased carriers of incurable afflictions, like smallpox and bubonic plague, as a means to justify anti-immigration policy and to drum up hysteria against Asian immigrants, who were perceived as a threat to white Americans for jobs.

The similar association between disease and immigrants was used as a catalyst for immigration restrictions on New York City’s Ellis Island in the 1920s. Tseng said the severity of and mortality associated with diseases originating in China, such as coronavirus and SARS, are quite serious, but often overblown.

“Certainly, this type of virus can start from any country. If there’s a certain mode of infection from an animal to a human that takes place, it can start anywhere,” said Tseng, who teaches a course on Asian American health. “But it’s certainly a concern to hear the news that different countries are confirming the ‘yellow peril’ and ‘yellow alert’ prejudices against people from China.”

While the coronavirus is responsible for more than 1,000 deaths and 43,138 infections, including nearly 500 cases outside of China, as of Wednesday, Tseng said public health officials are still gathering information, and that early estimates are that the virus will reach its peak of contagion in the spring, with potentially more than 200,000 cases by April.

“(The coronavirus) is a very serious issue, for sure, but from a public health standpoint, it’s a relative issue compared to all the public health issues out there globally,” he said. “Based on preliminary CDC estimates last week, our regular influenza virus has infected more than 20 million Americans and caused 12,000 deaths this flu season. This is probably a more serious issue right now in America.”

A state of anti-immigrant bias

A group of Asian women and children are detained at Angel Island in the early 20th century. Detainees were kept at the facility anywhere from two weeks to six months before being deported or let into the country. (Photo courtesy of Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation)

Berkeley professor john a. powell said the discrimination against Asians because of the coronavirus is due to a ‘heightened state of (anti-immigrant) bias’ in the United States.

As an example, a federal law was passed in 2018 to restrict Chinese student and scholar immigration to America. That prejudice, powell said, is an outgrowth of larger debates about trade, Chinese espionage and worries about the expansion of Chinese companies’ 5G broadband system.

Many of these debates, he added, are not about trade or free-market competition, but instead about preserving white American dominance.

Professor john a. powell is an expert on wide range of issues including race, structural racism, ethnicity, housing, poverty and democracy. (UC Berkeley photo)

“It’s an assumption that the West, particularly Anglo-American Christians, should dominate the world,” said powell, who is director of Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute. “So, somehow, Asians are seen as not real Americans and not to be trusted.”

According to the International Monetary Fund, in terms of gross domestic product and purchasing power parity, China’s economy is the largest in the world, at $25.27 trillion. The United States, in comparison, sits at just over $21 trillion.

Tseng said China is increasingly perceived as the primary threat to America’s global dominance, and with economic and political tensions continuing to rise between the United States and China, Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans may be scapegoated for things other than the coronavirus.

“Many Chinese Americans have been here for many generations and are not coming from China or Wuhan,” said Tseng. “Often, from a historical standpoint, I really feel things in our anti-immigration climate may just get worse before they get better.”

Empathy for the infected

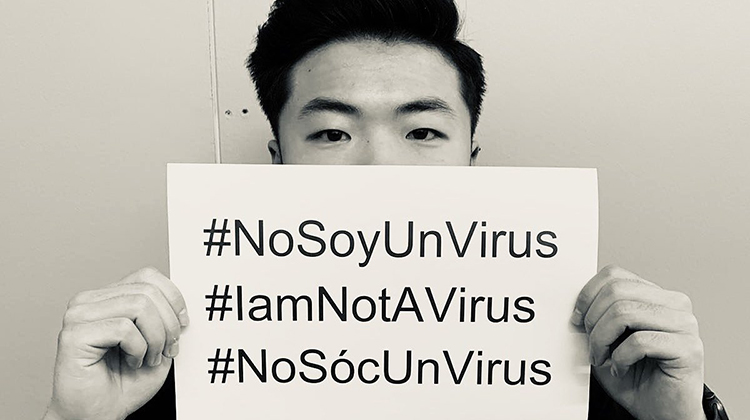

Jia Liang Sun-Wang, a Spanish-born Chinese man, holds a sign in response to coronavirus-based discrimination. (Photo courtesy of @JLSunW via Twitter)

Third-year Berkeley student Kolette Cho said she’s heard of instances where people of Asian descent have been discriminated against because they may have friends or family who have come from, or have visited, China recently.

But as a Korean American, she has not experienced any prejudice firsthand because of the coronavirus.

“I’ve heard of jokes that maybe it was an exchange student bringing (coronavirus) here, which can be kind of insensitive,” Cho, 20, said. “I don’t know if people mean it in a malicious manner, but I don’t think it’s beneficial.”

For powell, thinking about the infected and how we can help as a global society is important. He said changing the way we describe people from other cultures and countries is a step in the right direction.

“Sometimes they’re Muslim, sometimes they’re black, sometimes they’re Mexican, sometimes they’re Asian,” powell said. “But there is no them. There’s only us, and we have to figure out how to go forward where everybody belongs and nobody dominates. Not blacks, not whites, not Christians, not Muslims. No group dominates.”