Boalt Hall’s name is gone, but its history is examined in new exhibit

Berkeley Law's upcoming "A Time for Change" display is designed to remember, not forget, the past and to show the school's commitment to equity and inclusivity.

May 14, 2021

A draft of the concept design by the Maude Group of what the “A Time for Change” exhibit could look like when it opens at Berkeley Law in mid-August. (Concept design by the Maude Group)

After UC Berkeley leaders unnamed Boalt Hall in January 2020, metal lettering spelling out the name on Berkeley Law’s west classroom wing was chiseled off by a work crew, clankily tossed in a box and carted away.

But the name’s removal — due to the racist views of 19th century Oakland attorney and building namesake John Henry Boalt — is just one step of several being taken by the law school in its endeavor to examine, not simply erase, Boalt’s more than 100-year legacy at Berkeley Law, as well as to further a sense of belonging for its increasingly diverse community.

John Henry Boalt’s virulent, anti-Asian racism fueled existing national prejudice against Chinese immigrants and led to Congress enacting the Chinese Exclusion Act, which, by 1902, led to a permanent ban on Chinese immigration. He also made isolated racist remarks about Africans brought to this country as slaves and about Native Americans.

Letters that spelled Boalt Hall were removed from the Berkeley Law’s west classroom wing on Jan. 30, 2020, following an announcement by campus officials that Boalt Hall had been unnamed. (Berkeley Law photo by Alex A. G. Shapiro)

By the time in-person classes start at the law school on Aug. 16, a new hallway display — tentatively titled “A Time for Change” — will provide context for how the role of the Boalt name on campus has evolved over time. Photographs of and quotes from those helping to pave the way for change at Berkeley, timeline information, as well as QR codes that viewers can scan to access documents related to the unnaming, are part of the installation.

“We’re not trying to whitewash history, and that’s the criticism of taking down the name from the wall — that you’ll just take it down and pretend it didn’t happen,” said Alex A. G. Shapiro, Berkeley Law’s executive director of communications. “It’s about grappling with and learning from what happened before, in order to go forward.

“And there’s something essential about showing your work that matters — how we got from one place to another — that we will demonstrate with this display, to have it there for people to walk by and learn from.”

This large lithograph of Boalt Memorial Hall of Law — today’s Durant Hall — recently was removed from the first floor of Berkeley Law’s North Addition to make room for the “A Time for Change” display. (Photo by Laurie Frasier)

The display, on the first level of Berkeley Law’s North Addition, will “put things into perspective. History is important,” added gar Russell, a Berkeley Law staffer on the 2018 Committee of the Use of the Boalt Name. Dean Erwin Chemerinsky assembled the group to research John Henry Boalt’s writings and beliefs and to recommend a response.

To make space for “A Time for Change,” a floor-to-ceiling lithograph of Boalt Memorial Hall of Law — a building that in 1911 became home to the fledgling UC School of Jurisprudence and is today’s Durant Hall — recently was removed. In 1951, when the school moved into a new, larger facility, the UC Regents renamed it the UC Berkeley School of Law; the name Boalt Hall then was given to the main classroom wing.

The law school’s dean, Erwin Chemerinsky, launched an investigation into John Henry Boalt’s racism. The resulting December 2018 report was then taken up by Chancellor Carol Christ’s Building Name Review Committee. It voted unanimously in fall 2019 to unname Boalt Hall, and the chancellor and UC President Michael V. Drake agreed. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

But for decades, many at Berkeley incorrectly referred to the entire building complex, and often to the law school itself, as Boalt Hall, and law school graduates often were called “Boalties,” a term of endearment for many of them.

John Henry Boalt’s views were discovered in 2017 at the campus’s Bancroft Library by Charles Reichmann, an attorney and Berkeley Law lecturer who was researching the Asian experience in California, and that revelation prompted Chemerinsky to launch an investigation.

The new display’s chronicling of the Boalt Hall story will include mention of Boalt’s wife, Elizabeth, who contributed, in memory of her husband, to the first law school building and whose portrait hangs in Berkeley Law’s Charles A. Miller lobby, said Charles Cannon, the law school’s senior assistant dean and chief administrative officer. A plaque will be added next to the portrait to contextualize her relationship with the school.

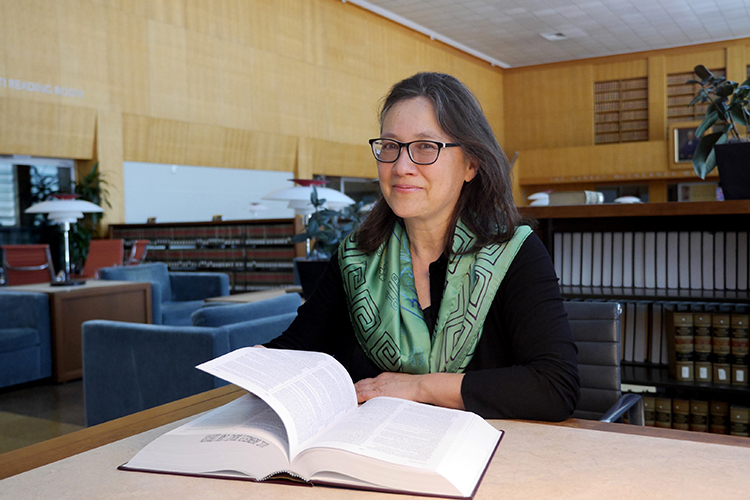

Leti Volpp, a Berkeley Law professor, served as the faculty representative on the 2017-2019 Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name and was lead drafter of its final report to Dean Erwin Chemerinsky. She will be highlighted in the new display. (Berkeley Law photo by Rachel Deletto)

“New students, as well as alumni returning to the building for reunions, will come to understand the complex history of what’s in a name,” said Cannon, who chaired the Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name.

Cannon added that casual usages at Berkeley Law of the name Boalt — in school newsletters, student organizations, the school directory and at numerous events and symposiums — have been ended.

“A Time for Change” also will include Attorney Quyen L. Ta, a 2003 Berkeley Law graduate and a member of the Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

A ‘visible public record’

In fall 2018, after Chancellor Carol Christ’s Building Name Review Committee had unanimously voted to remove Boalt Hall’s name, having received an unnaming proposal from Chemerinsky, the dean convened a group, the Visual Display Committee, to oversee several initiatives involving visuals and graphics at Berkeley Law. Currently, the faculty, staff and student committee is developing three installations, including “A Time for Change.”

“The Visual Display Committee’s initial and primary task was the development of a Boalt contextualization display … to explain the history of the confusion over the name of the school/building, Elizabeth and John Boalt’s early history with Berkeley and the process of denaming,” said Cannon, who chairs the committee.

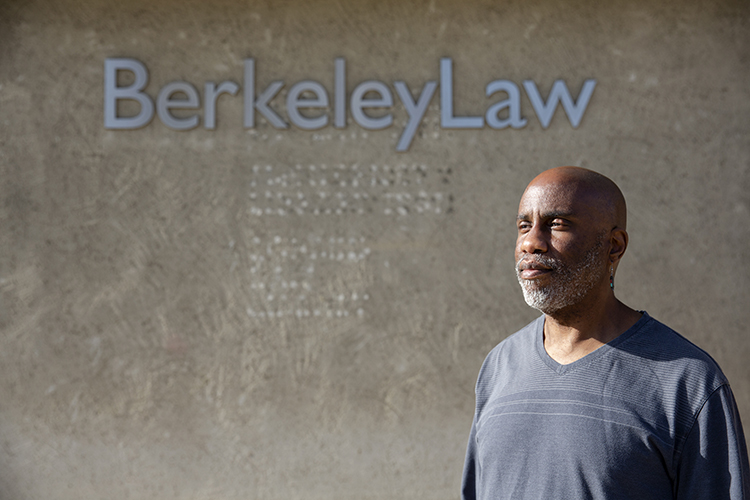

Berkeley Law staff member gar Russell, standing next to where the lettering for the name Boalt Hall was removed from Berkeley Law in January 2020, is part of “A Time for Change.” A longtime member of the UC Berkeley community, he was on the school’s Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

The committee has been guided by the Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name’s recommendation, in its report to Chemerinsky, that there be a “visible public record” — an exhibit, installation, plaque, sign or public art form — of the history of the Boalt name at Berkeley Law, so that viewers can acknowledge it. It also urged that the law school community be tapped for input.

Likewise, the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee said in its report to Christ that its recommendation to unname Boalt Hall “is not a suggestion that the legacy of John Henry Boalt or the donation of Elizabeth Josselyn Boalt be forgotten,” and that the law school must “engage publicly with Mr. Boalt’s racism, Mrs. Boalt’s philanthropy, and why our community removed the name from the building.”

Such engagement, it continued “must be done as part of a commitment to restorative justice. This is an opportunity to transform the building into a place of communal, cultural healing and to assert the centrality of Berkeley values in every aspect of the campus community.”

It was Charles Reichmann, an attorney and Berkeley Law lecturer, who discovered John Henry Boalt’s racist writings in 2017 while researching the Asian experience in California at the Bancroft Library. His photo also will be in the new exhibit. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Chemerinsky committed a total of $100,000 for the three installations in the works — two of them have not yet been made public — and the Maude Group, a content development company in Chicago, was hired.

The unnaming of Boalt Hall is one of a number of positive changes made at Berkeley Law since Chemerinsky became the school’s 13th dean in July 2017, said attorney Cheyenne Overall, a 2019 Berkeley Law graduate who was the student representative on the Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name. She added that “all of these changes endeavor toward a more inclusive environment for marginalized or underrepresented students.”

Attorney Cheyenne Overall, a 2019 Berkeley Law graduate, said she is encouraged that the school has enrolled more minority and female professors. Overall, another member of the law community to appear in “A Time for Change,” was the student representative on the dean’s Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name, which recommended unnaming Boalt Hall. (Photo by the ASUC Office of the Academic Affairs Vice President)

For example, said Overall, in 2017, there were only 12 Black students in the first-year law school class of 300. In 2018, there were 28 — the largest class of Black law students at Berkeley Law since the passage of Proposition 209. In 2019, there were 33, and in 2020, there were 41.

Another example, according to Berkeley law data, concerns Native American first-year students: In 2017, there were four, in 2018 there were 12. Seven were in the 2019 class, and nine in 2020.

Under the dean’s tenure, Overall added, “the law school also hired more minority and female professors and is doing a better job at supporting first-generation and public interest students.”

Alex Mabanta, a doctoral student at Berkeley Law who also is on the Building Name Review Committee and whose photo will be in the new exhibit, said UC Berkeley thrives most when its students “are engines of change. Each of us at UC Berkeley must be vigilant in creating a community we all belong to.” (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Since the 2018-2019 school year, according to law school officials, seven of Berkeley Law’s 12 new faculty hires were non-white — three were African American, one was Hispanic and three were Asian American. Of the 12 hires, five were women.

Russell added that Berkeley Law has had “an amazing parade of lunchtime workshops on various aspects of race and the law that put us in a place where we can really address these issues together.”

Chemerinsky will be sharing Berkeley Law’s work on the unnaming of Boalt Hall at an East Coast law school, where he was invited to appear on a panel about unnaming, as that school “is struggling with its name and wants to use his experience,” said Cannon.

Charles Cannon, Berkeley Law’s senior assistant dean and chief administrative officer, headed the Committee on the Use of the Boalt Name and runs the school’s Visual Display Committee that has three projects in the works, including the Boalt Hall conceptualization display. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

As for the future of the former Boalt Hall, which temporarily is being called The Law Building, Overall said she feels building names should be given “term limits.”

“People fail to notice that, without a limit, an honor is perpetual,” she explained. “And as long as a person holds an honor, the community is saying that that person should be honored. As communities become more diverse, and power is more equitably distributed, new voices ought to have a say in whether a person should be honored. The renaming process would give the community an opportunity to reflect on its values on a recurring basis and make a joint statement about who they are, and who they hope to become.”

In the meantime, said Shapiro, “we want students to feel that these are their halls. That Berkeley Law is elite, but not elitist. What’s on a wall, or what’s in a hall, should reflect the very people who are the students and the faculty and the community doing their thing in the building.”

Laurie Frasier, creative lead at Berkeley Law, confers with Alex A. G. Shapiro (right), the school’s executive director of communications, and Joe Maude of the Maude Group, about the design for the “A Time for Change” exhibit. (Photo by Rachel DeLetto)

“Especially as we’re moving from virtual classes to learning in-place, this idea of a sense of place becomes so much more obvious,” he added. “The environment in which we exist matters. When we return to these halls, there’s an opportunity to create community.”

Paul Fine, chair of the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee, said he hopes to see projects in the works that reckon with the racist legacies at the other three sites on campus that have been unnamed in the past 16 months — LeConte, Barrows and Kroeber halls.

“Simply taking a name from a building is only an important first step, and the university needs to follow through with more substantive actions,” he said. “I am glad that Berkeley Law is doing this, and I hope that there will soon be other actions taken for the other buildings.”