En pointe for her Ukrainian culture

In a Fiat Vox podcast episode from 2019, UC Berkeley staffer Erika Johnson discusses why her family fled Ukraine after World War II and how ballet connects her to her culture like nothing else does.

June 4, 2021

Fiat Vox is going on summer break! We’ll be back with new episodes in mid-August. In the meantime, we’ll be revisiting some of our favorite episodes. Here’s one from 2019 about UC Berkeley staffer Erika Johnson, who talks about why her family fled Ukraine after World War II and how ballet connects her to her culture like nothing else does.

(Today, Erika is a development coordinator on the major gifts team with University Development and Alumni Relations (UDAR) at UC Berkeley. When this episode first came out, she had a different position with UDAR.)

Erika Johnson is on the major gifts team with UC Berkeley’s University Development and Alumni Relations. (UC Berkeley photo by Anne Brice)

Read a transcript of Fiat Vox episode #78: “En pointe for her Ukrainian culture.”

This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: “Highride” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Before we revisit an episode from 2019, I wanted to let you know that Fiat Vox is going on summer break. We’ll be back with new episodes in mid-August. In the meantime, we’ll be re-sharing some of our favorite episodes from our archive.

Today, we’re sharing an episode about Erika Johnson, who works on staff at UC Berkeley, about how ballet kept her culture alive after her family fled Ukraine after World War II. Okay, here’s the story.

[Music fades down]

When Erika Johnson was 7, her Ukrainian mom put her in ballet class.

[Music: “Alchemical” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Erika loved it right away. The structure and repetition appealed to her need of order. There was a right way of doing everything, and if she practiced hard enough, she could usually get it right.

Erika Johnson: In a world that could be chaotic and unpredictable, ballet class was always something that I could go back to with reassurance.

By the time she was 13, a lot of dancers her age had dropped out. It was hard to maintain a rigorous training schedule and be a normal social teenager.

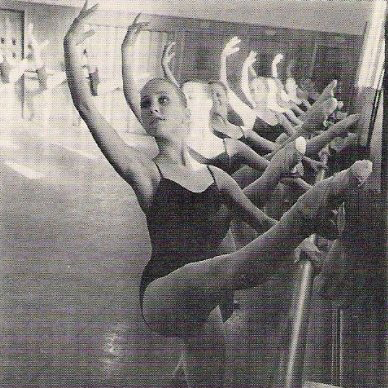

Erika (front) studied ballet at Marin Ballet as a teenager. (Photo courtesy of Erika Johnson)

Erika was tempted to stop from time to time, but she just couldn’t give it up. She loved performing. She was shy, but not on stage, with the bright lights and music. It was a place where she could transform into someone else — someone bold and confident.

Although she didn’t have the body that most principal dancers were known for — tall with long legs and super-flexible arches — she had the work ethic that it took to be successful.

Erika Johnson: I think the reason maybe why I persevered is because it was not handed to me. It was never even quite mentioned to me growing up or as a teenager like, “Oh, my dear, you must continue. In fact, we want to personally train you in solo classes.” There was some interest, but it was never like, “I must hand pick you and cultivate you like a rose.” You know it was like, “If you work hard, you might get a job.” And I was like, “Okay, well I’m going to work hard.”

As a senior in high school, she was studying for the SATs and auditioning for ballet companies, thinking that if dancing didn’t pan out, she could go to college.

But at 18, her path was chosen. She was offered an apprenticeship at the Houston Ballet Company, followed by a company position the following year.

Three decades later, now retired from a long career in ballet, Erika — who worked for UC Berkeley’s Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies and recently moved over to University Development and Alumni Relations, reflects on the role that ballet has played in her life and how it’s helped keep her Ukrainian culture alive after her grandparents fled their country after World War II.

Growing up Ukrainian during WWII

Erika’s grandfather, Ivan Mikhail Shmilenko, was born in 1922 in a village near Kyiv, Ukraine. Dictator Joseph Stalin came to power two years later, and in 1932, he orchestrated a famine aimed at killing the Ukrainian peasant population.

As many as 12 million Ukrainians died in the genocide. But Ivan’s family survived — relying on extreme resourcefulness.

Erika Johnson: The way they survived is my grandfather’s father was a veterinarian on the collective farm — he took care of all the pigs — and he saved, pocketed pig feed, the feed that you would give to the pigs, and he brought it home to his family. So, that’s how they survived the famines.

Erika’s grandparents were one of millions of “Ostarbeiter” or “Eastern Workers” — people from Central and Eastern Europe who were forced to work in Germany — often in factories (pictured) and on farms — during World War II. (German Federal Archives photo via Wikimedia Commons)

When Ivan was a teenager, World War II started. Soon after, he was taken by German soldiers and forced into labor as one of at least 3 million “Ostarbeiter,” or “Eastern Workers” — people removed from Central and Eastern Europe to become slave workers in Germany.

Meanwhile, about 300 miles southeast of Kyiv, 15-year-old Alexandra was taken from her village in Zaporizhia and sent to work on a farm. She would become Erika’s grandmother.

Erika Johnson: She remembers being lined up with the other Ukrainians and then the German families would say, “I want that one to be my slave.” And she was taken into a German home at one point and the matron of the house said, “I’ll feed you well, but I’ll work you hard.”

And she was in charge of the cows. At one point, she lost track of one of the cows — she had to take them to water and to graze and she didn’t know, “Are they going to kill me when I get back and I’m missing one cow?”

The cow eventually showed up, so she didn’t have to find out. But this was how she and Ivan — and millions of other Ostarbeiter — lived during the war: Torn from their families, terrified that they’d be killed, continually victimized.

[Music: “Aourourou” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ivan and Alexandra lived in a displaced persons camp for several years, waiting to immigrate to the U.S. While in the camp, they had a baby named Tonia. (Photo courtesy of Erika Johnson)

For them, going back home would be dangerous. Those who returned, usually through forced repatriation, were often considered traitors and sent away to labor camps for “reeducation.” Those who were allowed to live in Ukrainian society faced discrimination and were denied basic rights.

In October 1945, though, the U.S. banned the forced repatriation of Ostarbeiter, so Ivan and Alexandra stayed in Germany for several years, until they could immigrate to America.

Erika Johnson: So, they never returned, and they never saw their family again. They waited to get a sponsorship to America. They probably could have gone earlier to perhaps, Australia or Canada. But they waited a couple of years in Germany until they were sponsored by a church in Portland that paid their way for a two-week boat ride across the Atlantic with many other immigrants.

They came to New York, then boarded a train across the country to Portland, Oregon, to start a new life.

Preserving culture through ballet

It was 1951 when Ivan and Alexandra made it to Portland. In Germany, they’d had a baby — Tonia — who was 3 when they got to the U.S.

After the family became American citizens, Ivan bought Oregon Roofing Company and became a successful business owner.

Erika‘s mother, Tonia, in Germany before her family immigrated to the U.S. Once they arrived in Portland, Oregon, Ivan put Tonia in ballet classes, as a way to keep their Ukrainian culture alive. (Photo courtesy of Erika Johnson)

And they did everything they could to keep their culture alive. Ivan, with his Ukrainian immigrant community, built the first Ukrainian Orthodox church in Portland.

Erika Johnson: They had the strongest church group of all Ukrainians, and they would get together and drink vodka and eat Ukrainian food in my grandfather’s home and do the hopak dancing. And he got the Ukrainian paper delivered to him. He was constantly reading like Solzhenitsyn — if I’m saying it right. Aleksandre Solzhenitsyn. And books — Tolstoy. He would read like War and Peace in Ukrainian cover to cover, trying to keep his culture.

And he put his young daughter, Tonia, in ballet.

Tonia and her two daughters, Erika (right) and Inger, on Mt. Tamalpais in the Bay Area. (Photo courtesy of Erika Johnson)

Erika Johnson: In Kyiv, (Ukraine), and in Russia, ballet is almost like, you know, the movies here. The state really supports ballet. Little schoolchildren are brought to see productions. And so, I think that my mother’s father instilled this respect for ballet in my mother.

As an adult, Tonia moved to the Bay Area, where she enrolled her two daughters, Erika and Inger, in ballet.

For Erika, ballet became her life — a powerful, beautiful and often silencing profession that meant everything to her.

[Music: “Our Son the Potter” by Blue Dot Sessions]

From dance to promoting the arts and Berkeley

At Houston Ballet, Erika was part of the corps de ballet — the members of a ballet company who dance together as a group. Think: the many snowflake dancers in The Nutcracker.

It’s repetitive work, she says, that requires precise uniformity among dancers. But there is a certain power, she found, that comes from a group moving perfectly together with such grace.

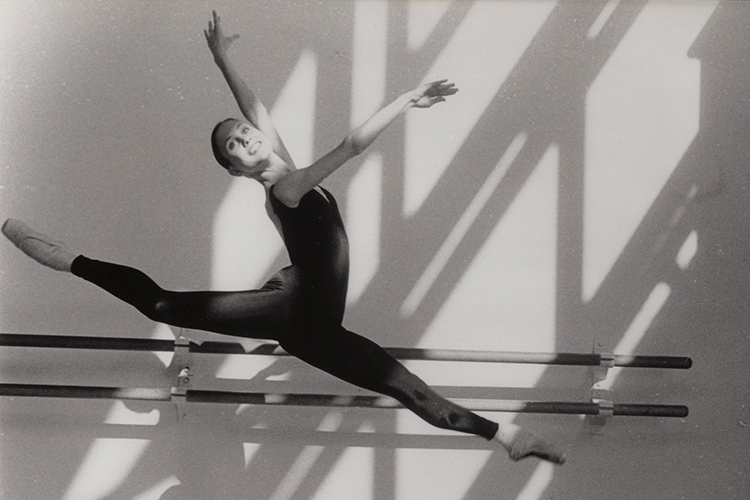

In 1996, Erika (pictured) joined Diablo Ballet, where she danced until she retired from ballet in 2010. (Photo by Ashraf Habibullah)

Erika Johnson: I have compared being in the corps de ballet to being in the military,” she says, “in the sense that even physically, the way you line up at a certain point in Giselle, I believe it is, is heel, toe, heel, toe — like when you run and you make a diagonal point and you literally have to stop directly behind the girl in front of you and line up the arch of your foot with the point of her back pointe shoe. And it happens one by one and it happens super fast and so, you see like 30 women lining up arch, point, arch, point. And it’s beautiful.

Being part of a hierarchical, large company, she says, also offered extraordinary opportunities, allowing the dancers to work with visionaries from around the world.

After seven years with Houston Ballet, Erika was ready to grow as a dancer. She joined a small company, Diablo Ballet, in Walnut Creek. As part of a smaller group, she was more often in the spotlight — with all eyes on her.

[Music: “Jog to the Water ” by Blue Dot Sessions]

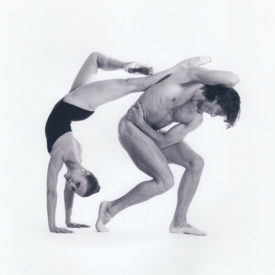

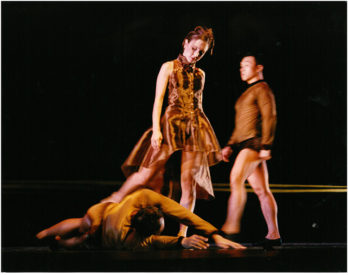

Erika performs “Walk Before Talk,” choreographed by KT Nelson for Diablo Ballet, founded by Berkeley alumnus Ashraf Habibullah and dancer Lauren Jonas.

(Photo by Scott Belding)

She spent the next decade imbuing her work on stage with depth and emotion. And becoming more confident in herself as an individual, away from the group.

As she neared 40, Erika knew she would retire from dance soon. Her body — always aching — was ready for a change. So, she started working as a development coordinator for Diablo Ballet — learning to apply for grants, work with donors and organize fundraising events.

In 2017, she joined UC Berkeley’s Theater, Dance and Performance Studies as an assistant director of communications and development, where she raised public and campus awareness of the department’s programs.

She says she appreciates how the department encourages artists to tell their own stories.

Erika Johnson: That has been so refreshing to me to hear. I do feel like, “Oh, perhaps if I had gone to college and joined a department like TDPS, that might have really helped my growth as a human, as a creative person.”

Erika danced professionally for two decades. (Photo by Weiferd Watts)

In January, Erika left theater, dance and performance studies for a position as a development associate in UC Berkeley’s Office of International Relations with University Development and Alumni Relations, where she assists with implementing programs that help to secure philanthropic support among international major gift donors. It’s a role that feels natural for her to step into, she says, joining a group of people who work with passion behind the scenes to create lasting relationships with the international community of alumni, parents and friends.

Erika’s grandfather, Ivan, ran Oregon Roofing Company until he died in 2012 at 89 years old. Now, his youngest son runs the company.

Her grandmother, Alexandra, still lives in Portland and just celebrated her 92nd birthday. Tonia, after raising her two daughters, moved back to Portland to take care of her parents.

In Berkeley, Erika takes ballet classes when she has the time. She says it’s like a language that she can speak again, connecting her to part of herself and her Ukrainian culture like nothing else can.