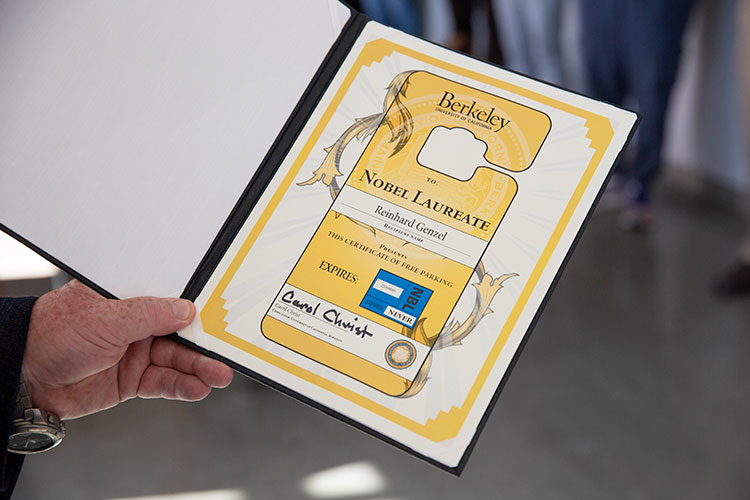

The biggest perk to being a Berkeley Nobelist? Free parking.

To celebrate Reinhard Genzel’s first visit to campus since the big win, Chancellor Christ presented the new physics Nobelist with a well-deserved free parking pass

July 28, 2021

To celebrate Reinhard Genzel’s first visit to campus since his 2020 Nobel Prize win, Chancellor Carol Christ presented him with his free campus parking pass at an event on Tuesday. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

When the customs agent at San Francisco International Airport asked Reinhard Genzel why he was visiting America, Genzel had a pretty good answer ready.

“I said, ‘Well, I’m an emeritus professor from UC Berkeley, and this is my first opportunity to return since becoming a Nobel laureate,’” Genzel said. “People nearby started clapping.”

Last October, Genzel won a portion of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for his precise measurements of the stars that swirl around the center of our galaxy, data that allowed him and his colleagues to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a black hole lies at the heart of the Milky Way.

Genzel, who has spent most of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, where he directs the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, said he is excited that it is finally safe to return to his “second home” at Berkeley. To celebrate Genzel’s first campus visit since the win, Chancellor Carol Christ presented him with one of the most coveted perks of Nobel laureate status — a free UC Berkeley parking pass — at an event on Tuesday.

Berkeley News spoke with Genzel about how his life has changed since the big win, what it’s like to observe the stars during a pandemic, and what he plans to do with the parking pass after he leaves Berkeley in early September.

Berkeley News: How has your life changed since winning the Nobel Prize in October?

Reinhard Genzel: Well, quite a bit, but not as much as some of my colleagues would have predicted. And you can imagine why: I think the traveling really would have been something! Sometimes I’ve given two talks per day in two different parts of the world, and Zoom is much easier, compared to doing that in the real 3D world.

The other part, of course, is interviews and radio shows. I wouldn’t have expected that the phase of intense bombardment would have lasted that long, and I guess that must have to do with the work I’m involved with: The prediction of this mysterious black hole fascinates many people, and yet they think that it is something they cannot understand. I’ve tried to find ways to explain it in somewhat understandable ways.

How does it feel to be back in Berkeley for the first time since your Nobel win?

For many years, Berkeley has been my second home. I was here full time in the 1980s, and that’s when my work on the galactic center started, with the very famous Nobel laureate Charles Townes. I’ve continued this work with different techniques and improvements during my time in Germany, but for the last 20 or more years, I’ve been (in Berkeley) twice a year for four to six weeks for teaching and research. So, it is great to be back, and I was sad that I couldn’t be here (for the Nobel win).

Free campus parking is one of the most coveted perks of Berkeley Nobel winners. “It certainly would have been great all these years, when I would always get in early to actually get a parking spot on campus,” Genzel said. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Why has it been important to you to keep this connection to Berkeley?

Personally, I love California, and my older daughter lives here and works here now, so there is a family connection. But, really, when we moved here back in 1980, we fell in love. It’s a wonderful place, Northern California. Of course, flying down here, it was sad to see those fires — those fires are terrible. But from a professional point of view, it’s nice to have fresh air and talk to my colleagues.

Have you been able to continue observing the stars during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Yes, we are observing as we speak, and last night was an excellent night. Fortunately, we are able to observe remotely (from an observatory in Chile). The observatory is more or less open now, although they are running with a lower fraction of people, so there are certain things they cannot do. But last night, I actually participated from (Berkeley), which was great.

We are building a major extension of the experiment we put together, where we’ve combined the light of all four of the 8-meter telescopes in a technique called interferometry. It’s very difficult, but it’s worked out, and we’ve had a lot of great measurements — not only of the galactic center, but also of other fields.

Do you have a favorite star or other celestial object?

No, not really, though you could say that the galactic center is, in a sense, our own laboratory at 27,000 light-years away. That’s where we go and do our experiments. It’s a very unusual situation in astronomy, because normally when we look at other galaxies much farther away, we might see their rotation, and we can measure their mass, and so, statistically, you can say something about [their motion], but you won’t see anything change. That’s where the galactic center is so dramatically different, because with the resolution we now have with this interferometry, we can see stars around the black hole zipping along and changing position from night to night. It’s just absolutely fantastic. It is very unusual to wake up on a daily basis and have data taken the night before show dramatic changes.

And these stars are moving so fast because they are close to a black hole?

Yes. The closest star, which we’ve seen this year, is about three times the distance away from the black hole as Neptune is from the sun. So, that’s pretty spectacular. They are moving at about 3% of the speed of light. And if you measure that well, you can start to see the effects of general relativity.

What are you planning on doing with your parking pass when you are in Germany? Can you lend it to someone while you are away?

I don’t know if I’m allowed to do that! I hear it’s not a hardware item anymore, you just give them your license plate number. But it certainly would have been great all these years, when I would always get in early to actually get a parking spot on campus. I’m certainly very appreciative of the value of it!

Genzel, who directs the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and lives in Germany most of the year, said he considers UC Berkeley his “second home.” (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)