Disabled and empowered: How Mariana Soto Sanchez found self-advocacy at Berkeley

"I always felt like I would place limitations on myself, but it's really just limitations imposed by society," says Mariana Soto Sanchez, who graduates this winter with a degree in media studies

October 1, 2021

See all Berkeley Voices episodes.

In January 2015, 15-year-old Mariana Soto Sanchez woke up one Saturday morning at her home in Ontario, California, with weakness in her hand. Within minutes, the feeling had spread throughout her body. Her parents rushed her to the hospital. By the time they got there, she had total paralysis. Later that night, they found out she had a rare disorder called transverse myelitis.

From that point on, Mariana had to adjust to an entirely new way of living.

Six years later, Mariana has regained some mobility and will graduate from UC Berkeley this December with a degree in media studies and a minor in journalism. She says she continues to learn how to advocate for herself in a world that isn’t built for her.

“I felt like I would place limitations on myself,” says Mariana. “But it’s really just limitations imposed by society that prevent me from achieving what I want to achieve.”

And she has done things she never thought she could — including going to her first Cal football game, a dream she had since she first came to Berkeley in 2018.

Mariana Soto Sanchez will graduate this December with a bachelor’s degree in media studies and a minor in journalism. (UC Berkeley photo by Neil Freese)

Read a transcript of Berkeley Voices episode #86: “Disabled and empowered: How Mariana Soto Sanchez found self-advocacy at Berkeley.”

Intro: This is Berkeley Voices. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: “Net and the Cradle” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Narration: Since Mariana Soto Sanchez started at UC Berkeley as a first-year student more than three years ago, she has dreamed of going to a Cal football game.

OK, so just to show you how fun a football game can be, if you don’t already know, which I’m sure a lot of you do, but anyway, here is a clip from 1982 of “The Play” during the Big Game between Cal and Stanford.

[Audio clip from UC Berkeley video “Cal Bears Football 82: The Play”: (Announcer is enthusiastically giving a play by play, cheering and yelling from crowd)]

Granted, this play is considered to be one of the most memorable in college football history. But exciting plays happen all the time and Mariana loves football and she has always just wanted to be there, chanting and cheering with the crowd.

But, for Mariana, actually attending a game seemed impossible — a feat that she just couldn’t manage on her own. Not only would she have to call the ticket office, request accessible seating and disclose her disability, but once she got to the game, she feared the disabled section would be in the least desirable place, set apart from the rest of the crowd.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: Just because I use a wheelchair doesn’t mean I don’t want to be in the middle of the chaos, too.

Narration: There have been a few times when she has bought a regular admission ticket to a concert and hung out right in the middle, in the pit, with everyone else.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: That’s been the most enjoyable, but at the same time, I risk my safety because, you know, people aren’t really conscious of someone in a wheelchair being there.

Narration: The built world, she says, is only accessible to some people. And many don’t realize that anyone at any time can become disabled and need accommodations that they didn’t even consider before.

Mariana with her mom, Francisca. (Photo courtesy of Mariana Soto Sanchez)

Mariana Soto Sanchez: Like, take me, for example. I didn’t really have any prior health issues, as opposed to someone who was born with a disability, they’ve always had that knowledge.

But it’s, like, OK, me, it’s like, now you have to adjust to a new way of living.

Narration: Mariana has used a wheelchair since she was 15, after she woke up one Saturday morning six years ago at her family’s home in Ontario, California.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: You know, I was on my phone checking what was going on, and then I was, like, “Oh, like, my back feels funny. Like, I probably slept wrong.”

Narration: She told her mom, who advised that she take a hot shower after breakfast to relax her muscles. So, Mariana poured herself a bowl of her favorite cereal, Lucky Charms, and sat down at the table.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I was, like, on my phone scrolling through social media and eating, and then my hand started feeling very weak. And then, it gradually became harder to pick up the spoon and stuff like that. It’s kind of like how it feels when you sleep on your arm, just, like, weakness.

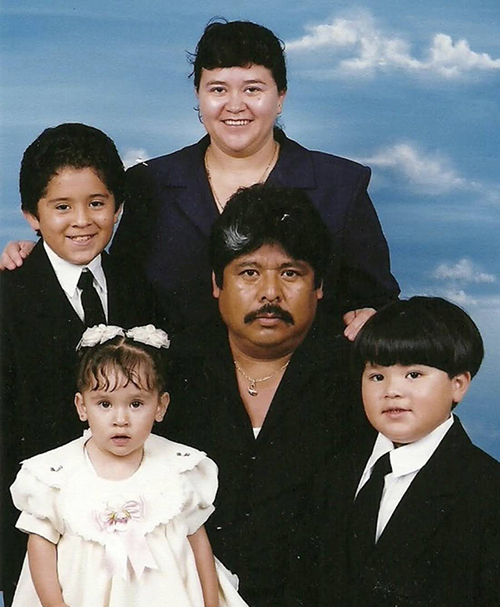

Mariana with her parents, Francisca and José, and her brothers, Erick (left) and Freddy. (Photo courtesy of Mariana Soto Sanchez)

Narration: So, she told her mom again, who was then talking to Mariana’s aunt on the phone. Her mom told her, again, that it probably wasn’t serious. That it would probably go away. Because, for a parent, these kinds of complaints from a child generally aren’t serious, and they usually do go away.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: And then it started to gradually spread to my whole arm. And then, my legs started feeling heavy, especially my thighs. And I was, like, “OK, Mom. Like, this isn’t normal. I think we need to go to the hospital or something.”

And then, when I told her, “Oh, yeah, my legs feel funny, it feels like I can’t walk,” she was like, “Oh, no, let’s go to the hospital.”

Narration: So, Mariana’s parents helped her into their car and made the 15-minute drive to San Antonio Regional Hospital. Mariana sat in her family’s black Ford Expedition, her dad trying to stay calm as he sped down the freeway toward the hospital.

To give you an idea of just how quickly this all happened: From the time that Mariana woke up with an achy back to when she and her family on their way to the hospital, only about 30 minutes had gone by.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: By the middle of the trip, that’s when I was, like, “Mom, I can’t feel my legs at all.” When I got to the hospital, I couldn’t get out of the car anymore. That’s when the paralysis spread to, like, from my neck to my toes.

Mariana and her brothers, Freddy (center) and Erick, at a Los Angeles Angels baseball game in the summer of 2019. After Mariana became paralyzed, Erick began to take care of her. This year at Berkeley, Mariana has a part-time caregiver whom she hired through a state program called In-Home Support Services. (Photo courtesy of Mariana Soto Sanchez)

Anne Brice: What were you feeling at the time? How were you… What was going through your mind?

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I mean, inwardly, I was really freaked out and scared because I was, like, “OK, if my hands and legs are becoming paralyzed and not working, it’s like, how much time before my heart stops, or I can’t breathe? So, I was very paranoid like that. I wasn’t even thinking, “Oh, am I going to get better?” I was thinking, “Am I going to die in a few minutes?” Because, obviously, I didn’t know what was going on. I was just, like, “OK, I woke up, and now I’m paralyzed. I can’t feel anything.”

But, like, outwardly, I was trying not to freak out because I didn’t want my parents to freak out. I was just very calm, like, “OK, something’s wrong, but they can probably give me a pill, and then it’ll go away.”

And, I remember just going there, getting checked in and then, in the waiting room.

Narration: After waiting for what seemed like forever, but was maybe more like two hours, she guesses, Mariana was finally seen.

[Music: “Vegimaine” by Blue Dot Sessions]

She was given a bunch of different tests over the next few hours. Then, Mariana and her parents waited for a diagnosis.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I was just there chillin,’ like in the bed, just only being able to move my head. And then, beside me, my mom’s crying her eyes out, like, “Oh, my God, what’s happening?”

Anne Brice: So, when did they finally figure out what it was?

Mariana Soto Sanchez: It was the same day, but it was a few hours after. It was late at night, like almost 11 p.m., when they finally said, “Oh, we ran some tests, and we think it’s transverse myelitis.”

After 2.5 months of intense rehabilitation following the onset of transverse myelitis, Mariana was able stand for a few minutes at a time and had regained partial use of her right hand. (Photo courtesy of Mariana Soto Sanchez)

Narration: Transverse myelitis is a rare disorder characterized by inflammation of a section of the spinal cord. Sometimes it’s caused by an infection, like influenza, or an inflammatory condition, like multiple sclerosis. And sometimes the cause is unknown, like it was for Mariana.

Although most people who have had transverse myelitis recover — at least, partially — long-term complications, like painful muscle spasms and partial or total paralysis, can linger.

After her diagnosis, Mariana was transferred to a children’s hospital in Orange County, then to Loma Linda University, where she did inpatient rehabilitation. After 2.5 months of intense rehab four to five times each day, she was able to stand for a few minutes at a time and had regained partial use of her right hand.

Anne Brice: And how are you right now? How does it feel right now?

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I mean, looking back, I feel like I’ve regained a lot, but at the same time, it’s not to 100%. I would say, you know, if I had to quantify it, like, maybe 65% to 70% of mobility.

I guess, in terms of feeling, it’s been pretty stagnant for, like, over a year or two, but what has been improved is, like, my endurance in doing activities. So, you know, before, even taking a shower with assistance was just, like, this huge task. Doing it, that was the only task I could do for the day before I was like, “OK, I can’t do anything.”

And now, I can shower sometimes without assistance, and then I still need a little breather, but then I can continue on with my day. And then, also, in terms of walking, before it was, like, virtually no walking. And now, because my apartment is kind of small, I walk around with my forearm crutches there.

Mariana, with her mom, Francisca, during Golden Bear Orientation in 2018. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Narration: I actually met Mariana when she started at Berkeley as a first-year student in 2018. She was 18 at the time and was with her mom, Francisca, at Golden Bear Orientation, where new students get to know the campus before their classes begin.

Here we are talking on Lower Sproul Plaza a few days after she’d come to campus about why she decided to take the leap and attend Berkeley:

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I’ve always been sheltered in my home, and I’ve never really taken any big risks because I’ve always been scared, like, “Oh, my God. I can’t do this.” And my cousins and therapist were like, “You know, we’ve been training for this — you’re ready to go out in the world.”

My first day here, I was, like, “Oh, no. I hate it.” I made a mistake. I called my cousin crying, and she was like, “No, you can do this. If we didn’t think you could do it, we wouldn’t have told you to come here.”

Narration: As time went on, it got better. She signed up with the Disabled Students’ Program and got the accommodations she needed for her classes — including a notetaker and extra time on exams. She found flatter routes on the very hilly campus and figured out how to get to each of her classrooms.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: In a lot of buildings, it’s like I have to go all the way through the back and then take an elevator downstairs and stuff like that. So, it was definitely a learning experience and, I mean, not always pleasant, especially when an elevator was out of service or there was construction here or stuff like that.

Narration: Her first year, she lived on the first floor of Cheney Hall, which was actually the second floor. The elevator would be out all the time. So, she’d have to call the front desk and someone would help her down the stairs and another person would carry her wheelchair for her. Every day, she’d leave an hour early for class, in case the elevator was broken.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: It’s amazing how much Berkeley has such a rich history in the disability movement, but there’s like, I mean, there’s stuff they can improve.

Berkeley disability activists Herb Willsmore (left) and Ed Roberts attend a Cal football game in 1969. (Photo from the Disabled Students’ Program photograph collection, UARC PIC 2800H:007, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Narration: UC Berkeley was one of the first campuses in the U.S. to begin accommodating students with disabilities. It began with student activists, who pushed the campus to provide equal learning and living opportunities for people with disabilities.

This activism helped ignite a national disability rights movement that gained momentum alongside the civil rights and women’s movements of the 1960s and ‘70s.

[Audio clip of the documentary, “The Power of 504,” by the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund: (News announcer) “Well, Isabelle, what’s going on now is an overnight sit-in. Actually, the demonstration is going on throughout the entire nation — in Washington, in New York, in Denver and here, in San Francisco. It all started this morning here at the old federal building at 50 Fulton Street when an incident took place outside. Immediately after that demonstration this morning, the handicapped started invading the building. It’s the old federal building, which is now the HEW headquarters. They spent most of the day in the office of the regional director here.” (Group sings) “I do believe that we shall overcome some day.” (Chants) “Sign 504! Sign 504! Sign 504!”]

In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act, or the ADA, was passed, which mandated equal rights and opportunities for people with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation and all places open to the general public.

Karen is an anthropology professor and chair of disability studies at UC Berkeley. She says that in the past couple decades, it seems as if disability rights activism on campus has waned.

Karen Nakamura, an anthropology professor and chair of disability studies at Berkeley, started the Berkeley Disability Lab in 2018. The lab’s motto is, “Making better crips since 2018.” (UC Berkeley photo)

Karen Nakamura: We had a really vibrant disability activism movement at Cal in the ‘70s and ‘80s. And then by the ‘90s and aughts, it started to dissipate. I think many of the people felt that once we had got the ADA, that that was the huge push, and that energy sort of evaporated.

And for about 20 years, you know, the situation’s been good, but not great. There hasn’t really been (much of a visible) disability culture at Cal (in the 2000s), per se. And I think what we’re (finally) finding in the last maybe five years is that students are realizing that they have to be more active. I think they realized that the real world looks accessible, but in reality, it isn’t. We’re not being taught the skills or being given the tools we need to succeed.

Narration: In the past few years, however, Nakamura says, the campus — under the leadership of Chancellor Carol Christ — has demonstrated a renewed commitment to making the campus a better, more accessible place for people with disabilities.

In 2018, Nakamura started the UC Berkeley Disability Lab, a purposefully disabled-led and disability-centered, accessible and cross-disability inclusive makerspace, research lab and teaching space. It aims to connect disability research, media and design in the Bay Area.

One project among several that the lab is working on is to create a free, open-source mapping and navigation app that embodies the knowledge and ways of disabled students and professors. The lab is also working to produce information and put on workshops to better help the disability community prepare for natural disasters and regional emergencies, like wildfires, power shut-offs and earthquakes.

[Music: “Allston Night Owl” by Blue Dot Sessions]

In 2020 — the 30th anniversary of the ADA — student activists secured a space in the Hearst Field Annex for a disability cultural community center, two doors down from Nakamura’s lab.

Alena Morales graduated last year with a bachelor’s degree in nutrition sciences and a minor in disability studies. She and a small group of other disabled students, staff and faculty had been advocating for the space since 2017. Alena says she hopes the community center will be a space where people with all different disabilities can come and feel “unapologetically disabled.”

Alena Morales, who graduated last year with a bachelor’s degree in nutrition sciences and a minor in disability studies, began advocating for a disability cultural center in 2017. The center is expected to open this January. (Photo by Cynthia Basa-Morales)

Alena Morales: I think it’s something that’s just been talk since I got to Berkeley as a student. You know, you go to DSP and you get your accommodations. But there’s really not a place where you can go and feel community in an identity-based way or sociocultural way.

It’s not the first time the community has rallied for one. Several advocates have done it since, man, since decades. I know one advocate that has been around for about a decade on the campus and was advocating for one. So, it’s not the first time that we’ve rallied for one. And the fact that it actually pulled through is amazing. But it’s something that we’ve needed for a while and it’s really long overdue.

We had a protest at one point, and one of our chants was, “What do we want? A community center! When do we want it? Ten years ago!”

Narration: Although the center’s opening was delayed because of the pandemic, organizers say it will open its doors this January and will hold a grand opening celebration in April. (This October, for National Disability Awareness Month, the center will host a virtual event every Wednesday, beginning on Oct. 6. Learn more about the center’s upcoming events.)

Mariana says that having a center where she could connect with people from the disabled community at Berkeley would have given her a certain kind of support that she hasn’t felt during her time at Berkeley.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: Yeah, I mean, I feel like I haven’t really encountered a lot of other disabled people, and that’s one of the main reasons that I say to other people, “Do what I didn’t, because it’ll make your life easier.”

When I have interacted with other disabled people on campus or online, I don’t know, something clicks, you know, what’s missing in other friend groups clicks because it’s like, they know the struggle of having to cancel a plan last minute because you’ve got a flare up of pain or, you know, just like not being able to be spontaneous in going out because you have to plan and see: Is there an accessible bathroom here? Are there ramps or other stairs? How am I going to get there? Is there public transportation and stuff like that?

It’s something that other people don’t normally think about, but it’s ingrained in other disabled people — it’s our culture. So, I don’t know… there’s comfort in understanding.

Narration: When COVID-19 moved classes online in March 2020, Mariana moved back to her parents’ house in Ontario and was able to attend virtual class from there.

When she was on campus before the pandemic, her mom had moved to Berkeley to help Mariana with everyday tasks. But when campus reopened this fall, her mom wasn’t able to move back to Berkeley, so Mariana had to hire a part-time caregiver through a state program called In-Home Support Services, which pays for 155 hours of care per month or about five hours a day. Her caregiver, Hazel, helps Mariana do things, like cook, grocery shop, do her laundry and organize her room.

Although Mariana was really nervous to be on her own for the first time, she says that she realizes now that it was the push she needed to do more on her own.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I mean, I was telling my mom how it was crazy how independent I could be. One of my biggest fears is not being able to do it and failing at doing something. And I guess I’m partially really glad that, you know, I was kind of thrust into having to be independent, having to find ways to do things for myself because it’s been liberating not having to rely on people to do certain things for me.

Before coming here, I was so worried. Like, every day, I would wake up feeling all panicky and nervous about what was going to happen. I felt like, coming here, I was just going to wither away, not being able to do anything for myself and then, just being here, having what I feel like is a newfound freedom — it’s been exciting.

[Music: “Palms Down” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Narration: This December, Mariana will graduate with a degree in media studies and a minor in journalism. She says she’s not sure what she wants to do after she graduates — she might apply to journalism school or maybe pursue a career in news or sports or maybe freelance for a while.

But she does know that she’s come a long way in her past 3.5 years at Berkeley.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: My social worker was talking about how a lot of people, especially people with disabilities, aren’t able to go to college because of all these roadblocks. It just got me really thinking, like, “Oh, man. How lucky am I to be, like, right at the finish line of graduating?” And then, just this immense privilege of being one of the few people with disabilities to be able to graduate.

Mariana’s view from the accessible section at a Cal football game in September 2021. It was at the top, separated from the crowd. “Just because I’m use a wheelchair doesn’t mean I don’t want to be in the middle of the chaos, too,” she says. (Photo courtesy of Mariana Soto Sanchez)

Narration: A couple weeks ago, she went to her first Cal football game. She figured she’d just buy a ticket and figure it out when she got there. She arrived two hours early to give herself plenty of time.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: And so, I just kept asking around, like, “Hey, do you know, first, if there’s an accessible section in the student section? And then, if there is, how do I get there? If there isn’t, how do I talk to someone into getting accessible seating?”

And I mean, I was like, going back and forth because someone was like, “Oh, talk to this person.” And I would go over there and then they were like, “Oh, no, actually, go talk to this person.” But thankfully, we figured it out. And there is accessibility seating in the student section, which I was very happy about.

Narration: She says it wasn’t in the best location — she had to go to the top and it was kind of removed from the action and energy of the game. But it was still exciting, she says, and plans on going to all the home games — something she wishes she’d done sooner.

Mariana Soto Sanchez: I feel like now I have more confidence to be able to venture out and knowing, like, maybe I can do these things that I thought I couldn’t before. And if I can’t, then I’ll know that these are my new, I guess, limitations.

During the summer, a disabled activist, Judith Heumann, released a memoir, and it was very eye-opening and inspiring. On living with disability, she said, “In my own mind, there were no barriers to what I could learn or what I could achieve. All the barriers came from outside of me.”

And that really stuck with me because it’s like, wow, I hadn’t really thought about it like that. Because I felt like I would place limitations on myself, but it’s really just limitations imposed by society that prevent me from achieving what I want to achieve.

Outro: This is Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast.

You can find links to disability resources on campus in this story on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts, where you can also read a transcript and see photos.

If you would like to hear more stories about the people that make UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is, subscribe to Berkeley Voices and give us a rating wherever you listen to your podcasts. Look for new episodes every other Friday.

Listen to other Berkeley Voices episodes: