For Berkeley alternative-energy project, big changes on the horizon

The Helios Energy Research Facility appears close to finding a new home west of the Berkeley campus — and to replacing a shuttered neighborhood eyesore with an eco-friendly building and public open space designed to spur downtown revitalization as it seeks solutions to global climate change.

January 11, 2010

The Helios Energy Research Facility, originally proposed as a hillside headquarters for Berkeley-based alternative-energy research, appears close to finding a new home west of the Berkeley campus — and to replacing a shuttered neighborhood eyesore with an eco-friendly building and public open space designed to spur downtown revitalization as it seeks solutions to global climate change.

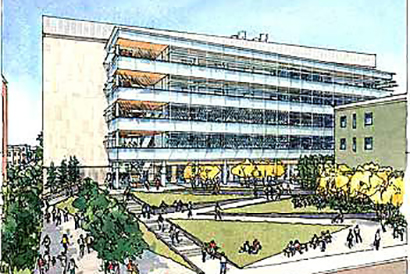

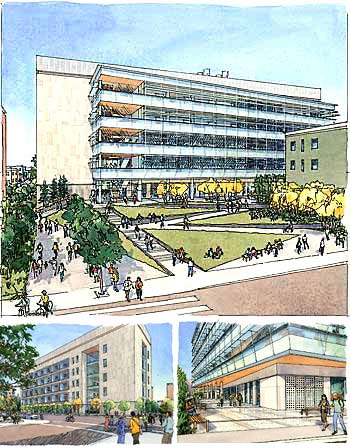

Three views of the proposed site. Top, looking north, a publicly accessible green plaza between Berkeley Way and the entryway to the new five-story Helios structure on Hearst Street, between Walnut and Oxford streets. Bottom left, a pedestrian pathway connects sections of Walnut Street long blocked by the old DHS building. Bottom right, looking west from Oxford. (Artist’s renderings by Jennifer Mahoney)

The brainchild of former Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory director Steven Chu — now head of the U.S. Department of Energy — the Helios project was initially slated to be housed in a large structure, to be built in Strawberry Canyon, for LBNL and UC Berkeley scientists working on solar energy, biofuels, and other ways to curb global climate change.

Now, under revised plans set to go to the UC Board of Regents next week, alternative-energy research will be more dispersed. If approved by the regents, a new five-story, 112,800-square-foot structure will rise on a university-owned lot just west of the central campus. Research there would focus on carbon-neutral biofuels, and would be conducted chiefly under the auspices of the BP-funded Energy Biosciences Institute and Berkeley’s bioengineering program.

Then, at some point in the future, a smaller building would be constructed on university-owned property at the LBNL campus. This scaled-down, 21,000-square-foot facility would be the new home of the Solar Energy Research Center, which is working to develop photovoltaic and electrochemical solar-energy systems.

Smaller, friendlier, greener

Bounded by Oxford Street and Shattuck Avenue on the east and west and Hearst Avenue and Berkeley Way on the north and south, the downtown site was vacated by the state Department of Health Services in 2006. It currently features an unused, Eisenhower-era institutional building abutted by parking lots.

By 2013, when Energy Biosciences Institute researchers are expected to move into the building west of campus, the property will have been transformed into a modern, accessible space in keeping with the city of Berkeley’s goals for downtown renewal. Among other improvements, it will offer neighbors a public, park-like area on the south, as well as a wide pedestrian pathway along Walnut Street, which now stops and starts north and south of the hulking DHS structure.

“Through our conversations with the community during the downtown-plan process, we got a very clear sense of the changing aesthetics the city would like to see in terms of redevelopment of that area,” says Jennifer McDougall, principal planner with the campus’s Capital Projects department. “Among the requests we heard repeatedly from the community were that there be more open space, and that Walnut Street continue through our site.”

Seen here from Berkeley Way, the existing site — extending from Shattuck Avenue to Oxford Street — features the hulking, long-abandoned DHS building and surrounding parking lots. (Peg Skorpinski photos)

The existing building, McDougall adds, has “hazardous-materials issues,” including the presence of asbestos and lead. By remediating and demolishing it, as was done with Stanley and Warren halls, “the university is providing a public service.”

Community response to the plans, she notes, has been overwhelmingly positive. Where concerns have been raised by neighbors and city officials, architects have made changes — as, for example, with the original design of the building’s north façade, which some found too “monolithic” for its residential surroundings. “There’s a lot more articulation in the façade now,” McDougall says, lending the structure a smaller, friendlier feel.

The building itself will go up along Hearst, on the eastern side of the pedestrian pathway. The western half of the lot is reserved for a future community-health campus, though the realization of that vision will have to wait for substantial improvements in the university’s budget picture.

Climate change and public health

In fact, while the alternative-energy project is focused squarely on the problem of global climate change, the west-campus site was conceived with an eye on public health, explains Catherine Koshland, Berkeley’s vice provost of academic planning and facilities.

“That location had long been in the sights of the School of Public Health, but it was too big for just them,” recalls Koshland, a professor of engineering, environmental and health sciences, and energy and resources. Thus was born the concept of a community-health campus that might include optometry, neuroscience, and perhaps some clinical-psychology programs. “The idea was to bring together those units that had both teaching and service components related to the community.”

Meanwhile, in exploring alternatives to the Strawberry Canyon site for Helios — prompted both by increasing costs of site development and community concerns about the ecological impacts of a large facility there — campus officials began to consider carving out a quarter of the recently purchased DHS site for energy research.

“As we began to talk about things, we realized there are synergies — perhaps not immediately obvious — in the relationship among energy biosciences and climate change and health that would make co-location of Helios with the community-health campus a good fit,” says Koshland.

That, of course, was before the economic crash, and what Koshland calls “an absolutely abysmal state-funding situation.” Now, she says, a move by the School of Optometry from its Gayley Road location is unlikely, though “in the long run, it belongs downtown.” Public Health, by contrast, “is very actively pursuing support that would allow them to develop their portion of the campus.”

From eyesore to asset

For the near term, the westside structure will be shared by Berkeley’s bioengineering department and EBI, the bioenergy “think tank” funded for 10 years by energy company BP at Berkeley, LBNL, and the University of Illinois. The facility’s primary research objective would be to develop new generations of biofuels — efficient, carbon-neutral alternatives to corn-based ethanol, for example — coupled with a thorough examination of their potential environmental, social, and economic impacts.

Pedestrians traveling north or south along Walnut are now forced to detour — a nuisance that will be eliminated by the new pathway.

Susan Jenkins, EBI’s assistant director, calls the northwest-corner location “a good fit” for the institute, allowing scientists to remain in close physical proximity to campus scientists with whom they interact regularly — such as those in plant and microbial biology, agricultural and resource economics, chemistry, and chemical engineering.

“It keeps us tied to the campus community,” she observes, adding that both students and faculty will have easier access to the new building than they would to a Strawberry Canyon site.

The regents are expected to vote on the revised plans during their Jan. 19-21 meeting at UCSF Mission Bay. Already, the plans have been subjected to local scrutiny at a series of public meetings in Berkeley, from a community open house to official sessions of the city’s Planning Commission and Design Review Committee. As McDougall notes, residents’ feedback at these meetings and through the Downtown Area Plan process was key to transforming a neglected eyesore into a neighborhood asset.

“I don’t think there are a lot of private developers who are willing to create that kind of street-level public space on their properties,” ventures McDougall. “I think that was recognized by the Planning Commission. They don’t see a lot of projects come forward where a developer is saying, ‘We’re going to use a third of our lot for open space that the community is welcome to use.’

“We’ve heard, even from some of our fiercest critics, appreciation for the move to this site,” she adds. “I do think people will be happier to see this building than what’s there now.”