Who decides the difference between a cult and a religion? The IRS

“In some ways, the story of cults is way less sexy than outlandish beliefs or messiahs or UFOs,” says Poulomi Saha, a UC Berkeley associate professor of English who teaches a class on cults in popular culture.

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

June 16, 2025

What kind of person joins a cult? It might be hard to imagine what would lead someone to join a group like the Manson Family or NXIVM, or who would bequeath their life savings to a zealous leader or commit crimes for such a group. But these might be the wrong questions to ask, says UC Berkeley Professor Poulomi Saha.

“Nobody joins a cult,” Saha explains. Rather, they join what they believe is a really good thing. “We call it a cult when it goes bad.”

That good thing — a system of belief that is incredibly powerful to those who subscribe to it — becomes a cult when there’s harm involved, says Saha. Such groups often feature a culture of secrecy, a fear of social backlash and judgement among members, and charismatic leaders who claim to have access to a singular truth.

Netflix

An associate professor of English, Saha designed and teaches a course on cults in popular culture. Students examine what it is about cults — or “intentional communities,” as they call them in the class — that attracts followers. They even design their own intentional communities, often with Berkeley students in mind.

Together, they think through how feelings of loneliness and isolation could lead someone to join a community of people that promises devotional support and belonging. Those kinds of feelings are common to young people, Saha says, especially on big college campuses like Berkeley.

“The brilliance of Berkeley students is not only do they have book smarts, they also have a pretty remarkable emotional intelligence and willingness to be intellectually vulnerable,” says Saha. “They have the ability to say, ‘What’s the difference between me and this person?’ They’re willing to think about their own embeddedness in a way that’s quite revelatory.”

Saha says people weren’t always able to talk about cults in this way. Until recent decades, cults have been on the fringe of society, and not the kind of thing you’d see in popular movies and TV shows. To be fascinated by cults was taboo.

Today, however, Saha says we are more open than ever to the idea of cults and how appealing they can seem.

This article was adapted from a Berkeley Voices podcast episode. Listen to the original episode here.

“Cults offer something that we cannot have in our normal everyday lives,” Saha says. “Our students are looking at the world around them and seeing fairly limited economic possibilities. On top of that, they are looking at the real crisis of climate change. They’re looking at the scourge of war and mass civilian causality and thinking: ‘It doesn’t have to be this way. I don’t want the world to be this way.’”

Saha says an American fascination with cults is nothing new. In fact, the same thing happened decades ago in the United States in the wake of World War II.

The birth of the cult

In the 1960s, the U.S. was in a remarkable moment of economic prosperity. The GI Bill had made college more available to a growing American middle class. Unions were strong, allowing people to build intergenerational wealth through blue-collar jobs. People were buying houses that would be passed down to their children.

The American Dream felt accessible to many more people, says Saha. Yet not to everybody; as they are quick to point out, it still largely excluded those who were not white, heterosexual, college-educated and middle-class.

Those who didn’t have access to this growing prosperity resisted these popular ideas of American success, says Saha. Others were looking at the state of the world — marked by the Vietnam War, student protests and the demand for conformity to produce economic prosperity — and wondered why they were valuing material success while “the world was burning.”

You can see how mainstream America would very much want to limit the legitimacy of these alternate imaginations.

All kinds of social movements began to gain momentum, including student movements, anti-war movements, the civil rights movement, and feminist and sexual liberation movements. They were all pushing against society’s demands for the conformity and normativity of the 1950s.

“People, especially young people, start to say, ‘You know what? I don’t want to live in the suburbs, in a house that looks exactly like every other house and have 2.3 children and one American-made automobile and all these appliances, and a life that is just so normal.’”

Instead, they began to have “alternate imaginations” about what it meant to be prosperous, says Saha.

“You have people who suddenly, despite Cold War anxieties about communism, say, ‘Communal living makes a lot of sense. What if I don’t want to be married to one person and have children and do chores? What if I want to live in a shared household with a whole range of people and redistribute all of our needs, our economic needs, our social needs? We care for one another. We take care of children together. What if I want to live in a radically different way?’”

Hundreds of intentional communities sprung up across the country, including the People’s Temple, founded by Jim Jones, and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, which aimed to start a “psychedelic revolution” in the U.S.

“You can see how mainstream America would very much want to limit the legitimacy of these alternate imaginations,” says Saha. “You can see how hard American society might want to make it so the idea of living in a commune is unthinkable during America’s fight against communism.”

In response, they explain, the U.S. government weaponized the Internal Revenue Service, or IRS, to keep cults from gaining legitimacy.

The arbiter of cults

One of the academic definitions of a cult is “a new religious movement” — something that isn’t yet old enough to be considered a religion. But this isn’t quite accurate, says Saha, because a movement’s longevity doesn’t determine if it’s a religion or not. Rather, it’s the IRS that decides.

“Why is the IRS the true arbiter of cults in America?” asks Saha. “It’s because they’re the only ones who can designate to churches tax-exempt status. There’s a lot of draw to that. What religious or philosophical or spiritual group wouldn’t want to be able to accumulate money and not have to pay taxes?”

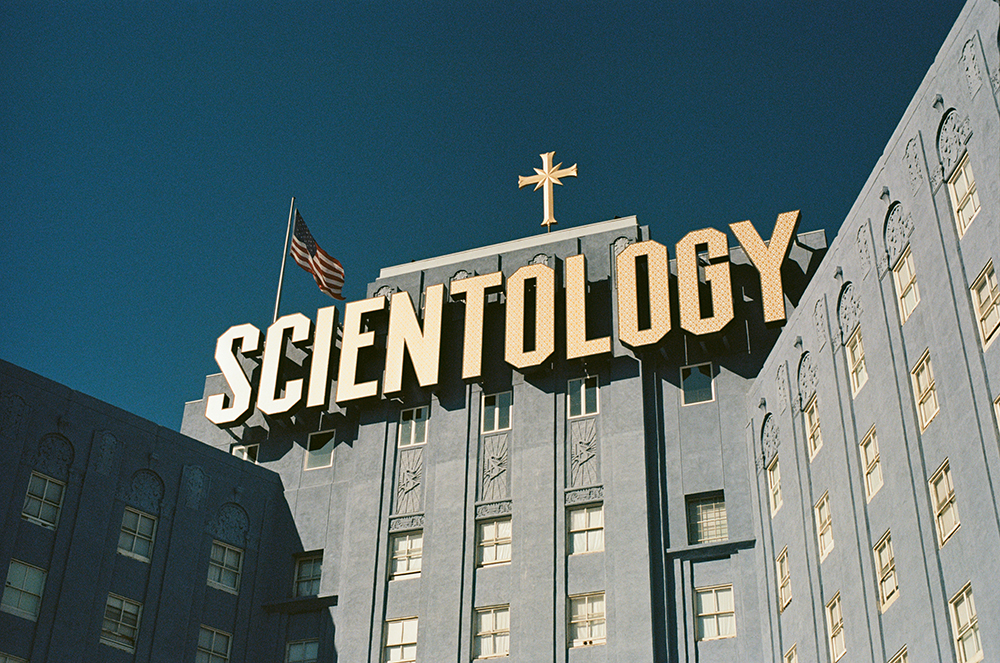

Scientology, Saha says, is a classic case. It has faced many cult-like accusations, like harmful secret behavior, disappearing followers and going to enormous lengths to silence opponents.

“The problem is not what people believe,” says Saha. “That Scientology is based on a story about UFOs is not the problem. Most belief, especially religious belief, is supernatural and extraordinary. That’s the nature of religion.”

The problem, Saha says, is the religion’s harmful practices. Since the Church of Scientology was founded in 1954, there have been thousands of complaints filed against it by former members and others alleging fraud, wrongful death, human trafficking and defamation.

It was even stripped of its tax exempt status in 1967 for more than two decades after its profits were found to be benefiting individuals and not the organization.

But because of the church’s enormous cache of money, says Saha, it has successfully fought these lawsuits and filed some 2,500 of its own against the IRS, winning back its status as a religion in 1993, which it has retained ever since.

“The reason that Scientology is a religion is because no one has been able to convince the IRS it shouldn’t be,” says Saha. “That’s what it comes down to.”

“In some ways, the story of cults is way less sexy than outlandish beliefs or messiahs or UFOs,” they add. “It’s really about whether or not you can convince the IRS that someone should pay taxes on the money donated to them.”

A tipping point

In the decades that followed the 1960s, Americans’ collective interest in cults faded.

Several high-profile groups, like the Manson Family, increased public awareness of cults and their dangerous effects throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. In turn, the social and cultural climate that first gave rise to them began to shift.

But today, Saha says, our fascination is back and is stronger than ever.

We’re in a moment in history, a kind of tipping point, where young people once again feel the weight of limited possibility. They’re saddled with debt and struggle to find jobs that pay enough to live, especially in the Bay Area.

What’s missing today, however, is what Saha calls a tug of economic possibility that existed in the 1960s.

“The promises of capitalism are already broken,” says Saha. “So they’re much more willing to take risks, to avow different imaginations.”

“Now, I’m not saying that they’re going to go out and join these groups,” adds Saha, “but they’re really unfettered from many of the things that were used to hold people inside the mainstream.”

Saha says our growing interest in cults is important because it tells us something about unmet needs in Americans’ lives. There are many modern practices and groups that could be considered cults, Saha says, but they are accepted by most people as having a positive effect on society.

Take the multibillion-dollar industry of yoga, for example, which could easily be rewritten as a story of a cult, says Saha.

“It is entirely socially acceptable to avow an obsessive attachment to yoga, to have it be a thing that transforms all aspects of your life,” Saha says. “Yes, your body, your mind, your spirit, but also your social life — what you wear, what you eat, how you walk through the world.”

But Saha isn’t interested in diagnosing people’s pathology or misidentified desires.

“I think people act toward their own happiness and their own desire often in very constrained circumstances,” says Saha, “and I don’t want to limit the access that people have to seeking it. My concern is always harm. That I’m deeply concerned about.”

So what should we do if a person we love joins what they see as a good thing, where they begin to experience a deep personal change that we don’t understand? What is actually happening during this transformation? And how can we reach them before we lose them?

“I am part of a growing cohort of scholars who are trying to understand this,” says Saha, “and I think one of the things that we have to do is drop our expectations of what we think is right and true.

“What would happen if we tried to listen and understand, even if we didn’t agree with those radical beliefs? I think we have to start there.”