UC Berkeley’s central news office marks 100 years of telling the university’s story

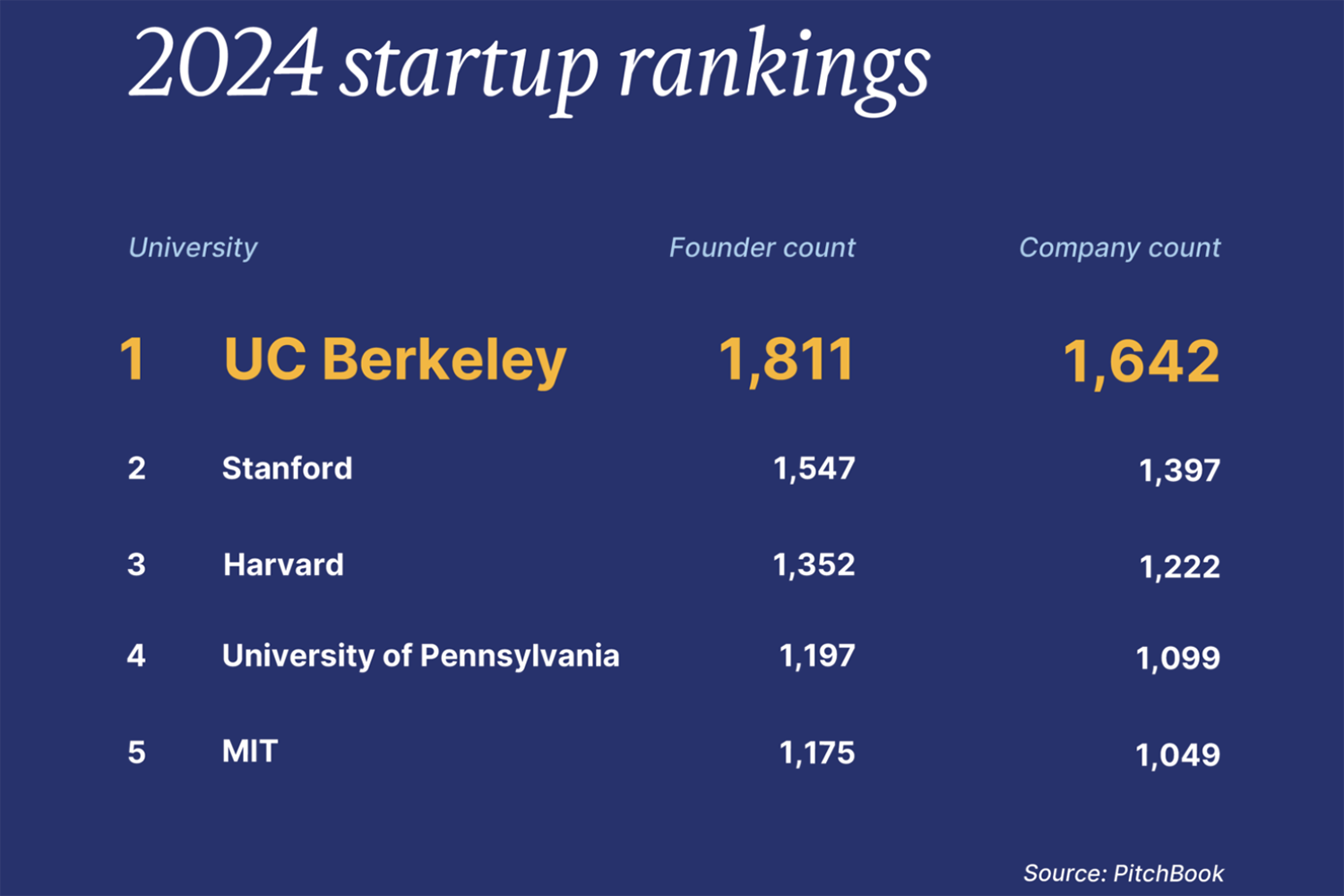

Berkeley's versatile communications team trumpets discoveries, innovations, top rankings, faculty experts and Nobel Prizes, while also handling difficult news.

July 1, 2025

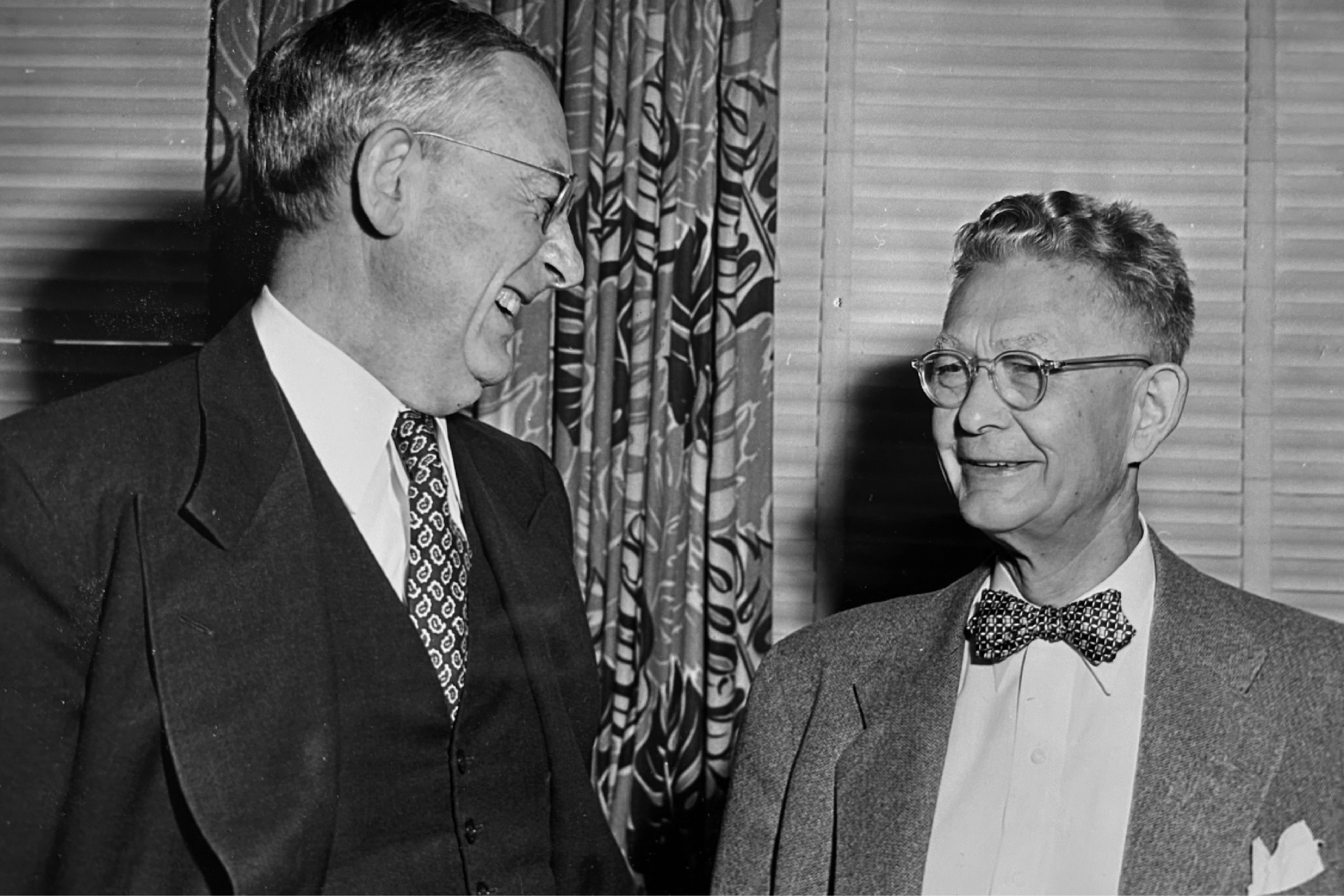

In 1925, a pipe-smoking, wisecracking journalist named Harold Ellis left the Sacramento Bee to open the University of California’s first news bureau. He was the “publicity man” that then-UC President Robert Gordon Sproul said he needed at Berkeley to help Californians understand the UC’s accomplishments — and its needs.

At the same time, professors were bemoaning inaccurate media coverage of their research findings, while the state’s newspaper editors claimed the university was uncooperative when they asked for information.

Single-handedly at first, and on a tight budget, Ellis traveled up and down California, building relationships with news editors. He launched the UC Clip Sheet, a weekly digest of news — not just from Berkeley, but from future campuses, like Davis, Riverside and Los Angeles, that then were considered UC outposts.

Those highlights, during Ellis’ tenure, would include invention of the atom smasher, or cyclotron, which eventually created 16 new chemical elements and garnered a 1939 Nobel Prize for Berkeley physicist Ernest O. Lawrence. The Nobel was one of the first won by a faculty member at any U.S. public university.

Lawrence Berkeley Lab archive

Ellis’ relationship with editors also is credited with helping with the passage in 1926 of California Prop. 10, which supported issuing $8.5 million in bonds to complete and equip state buildings, including classroom and research facilities at Berkeley.

Already by 1927, Ellis wrote in a report to Sproul that the University News Service he’d created had led the media to carry “a much higher type of news material. … The effect of this cannot be but for the benefit of the university.”

And locally, decades before San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen coined the term “Berserkeley,” newspapers were running fewer “objectionable freak stories,” Ellis added, “since we have been offering them … more worth-while material.”

The Bancroft Library

In its centennial year, today’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs continues to build on the pioneering work of Ellis and the news teams that followed. In addition to journalists, the group now includes specialists in social media, video and podcasts, marketing and digital communications, and strategic and critical communications.

As higher education faces sweeping changes from a new presidential administration, conveying to the citizenry how Berkeley’s research, teaching, scholarship and public service greatly benefit society is critical.

“Now, more than ever, it’s essential to Berkeley’s mission to tell our distinctive story effectively, transparently and comprehensively,” said Chancellor Rich Lyons, “and to replace caricatures about the campus with truth: Berkeley’s research greatly improves Americans’ lives, health and well-being, and our education lifts thousands of students up the economic ladder every year.

“We’re a unique societal asset, and our Office of Communications and Public Affairs is essential for gaining and sustaining support from the public we serve.”

UC Berkeley

A historic run of activism

When Ellis retired in 1950, the news bureau had a new name — the Public Information Office — and a home in Room 101 of Sproul Hall. And it no longer had a UC-wide focus: Ellis helped the UC’s LA outpost set up its own news bureau in 1927, Davis’ opened in 1949, and after the UC began reorganizing in 1951 into a multi-campus system, other locations followed suit, including at the centralized UC Office of the President.

The Berkeley office’s new name reflected additional work its growing staff was taking on — guiding campus tours for prospective students; running a speakers’ bureau; hosting visits by legislators and dignitaries; publishing an events calendar and a quarterly alumni newsletter; increasing the enduring UC Clip Sheet’s reach; and fielding thousands of inquiries annually from reporters, campus employees and the public. A walk-up window to the right of the front door — for in-person help — still is visible, although boarded up.

Over time, many of these tasks migrated to other units. But the news operation remained, eventually becoming UC Berkeley News and Media Relations, part of today’s communications and public affairs office. Throughout its history, its core role has been reporting major campus news, such as research breakthroughs, for the media and other audiences, and connecting reporters with faculty experts.

Jane Scherr for UC Berkeley

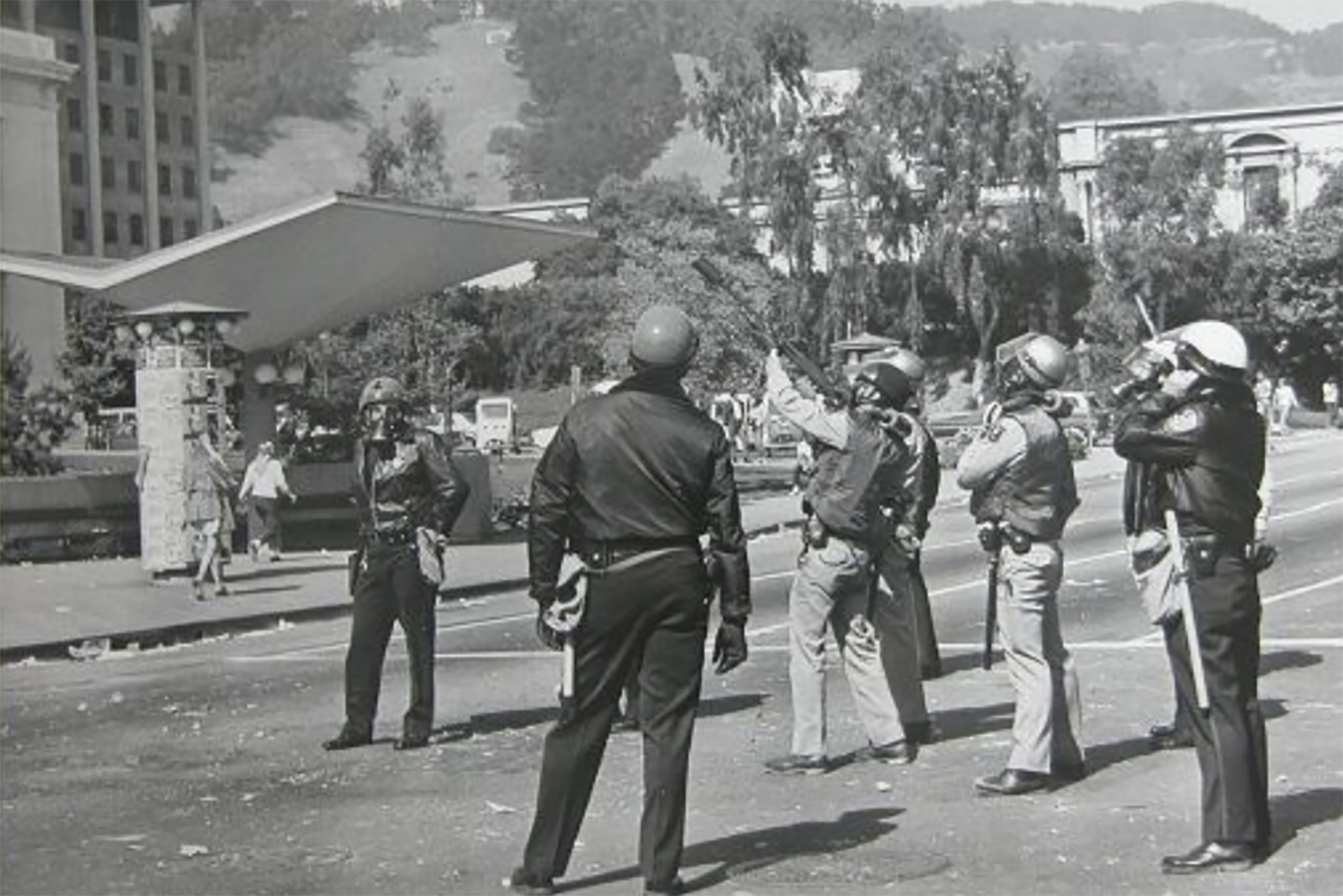

But in the ’60s, an additional role was honed: crisis communications. It was the start of a historic, decades-long run of headline-grabbing activism, including the Free Speech Movement, anti-Vietnam war protests, the Third World Liberation Front strike, anti-apartheid demonstrations and animal rights rallies.

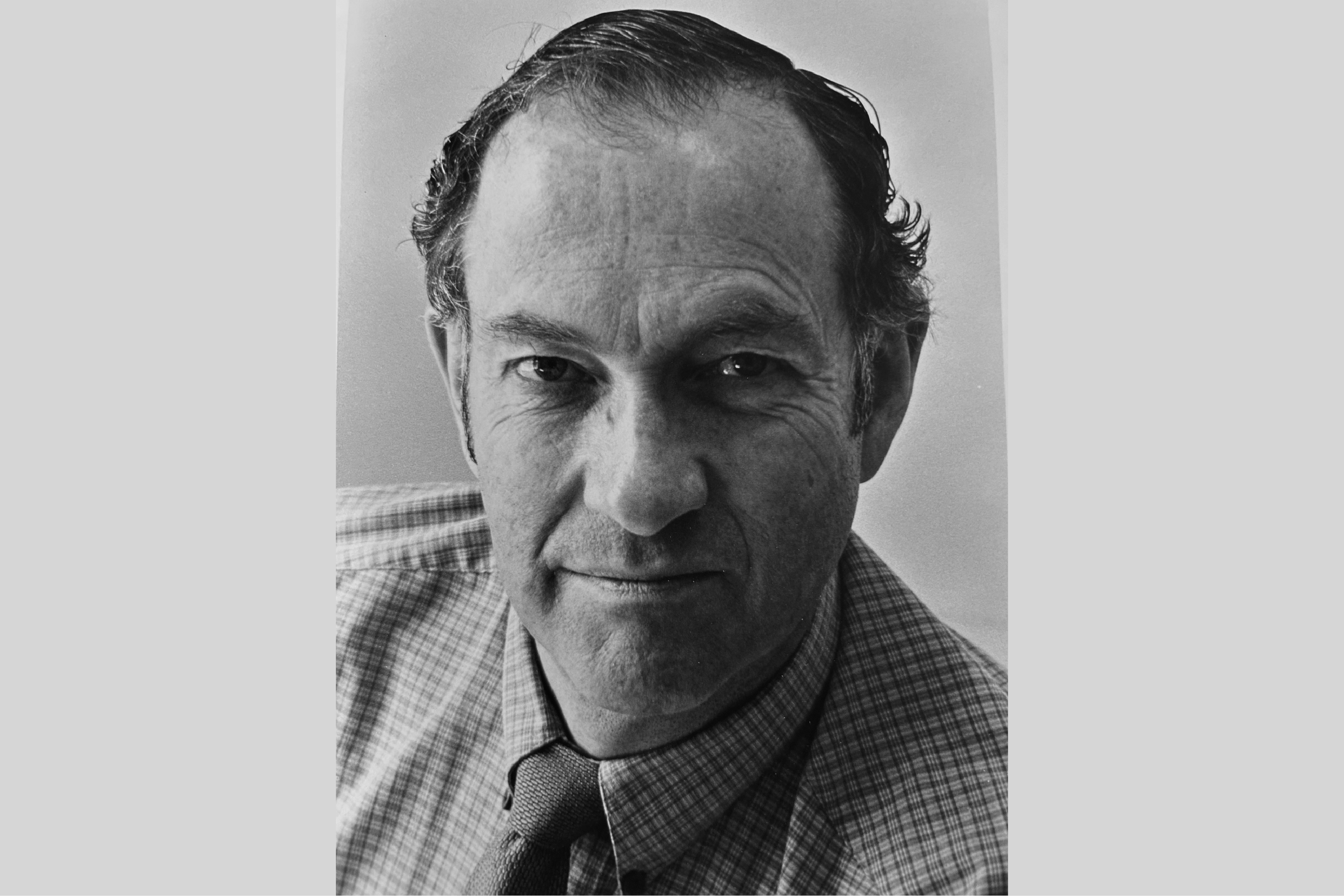

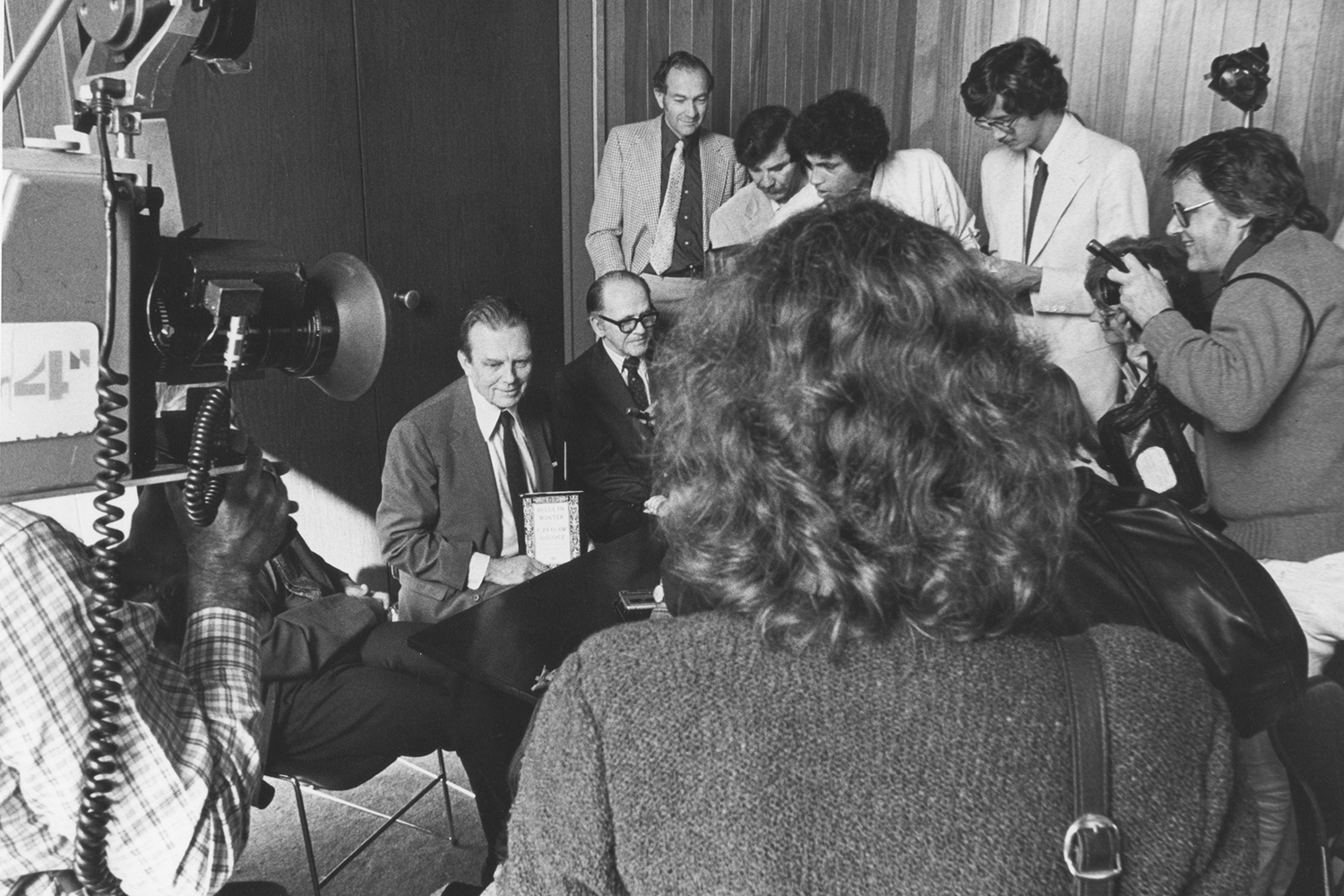

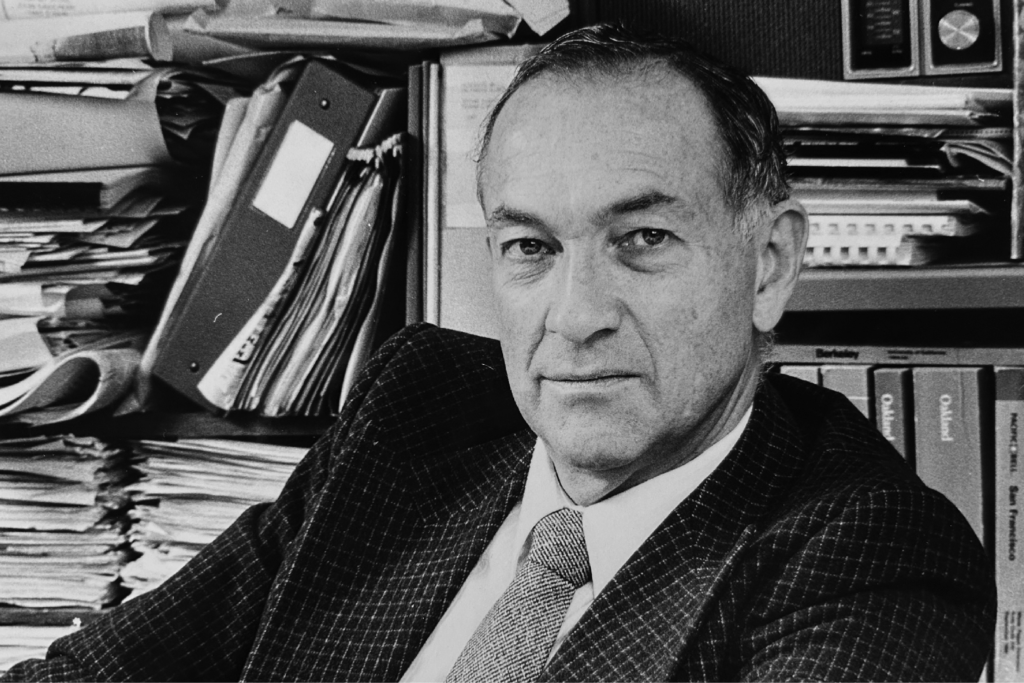

Ray Colvig headed the Public Information Office for 27 years, from 1964 to 1991. As campus spokesmen, he and his predecessor, Dick Hafner, “played a critical role, because there was so much media attention focused on Berkeley,” said John Cummins, chief of staff for four Berkeley chancellors, from 1972 to 2008. “ … They also built relationships with the media and … never tried to hide anything. They also were very respected by the faculty as having the campus’s best interests at heart.”

Lonnie Wilson/Courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

Colvig also did interviews, amid tear gas, during the 1969 People’s Park riots; handled global media interest in the 1974 kidnap and arrest of Berkeley student Patty Hearst; navigated heavy media interest in the ‘80s in violent acts by the Unabomber, a former Berkeley faculty member; and when the 1989 Loma Prieta quake struck, immediately went live with a New York radio station “for one hour, talking about it,” said Cummins. “That shows you a little about Ray’s … availability to act under lots of pressure.”

In September 1990, Colvig was at the scene of a 1 a.m. fraternity fire that killed three students. Just weeks later, a Berkeley student was fatally shot and six others wounded in a hostage crisis at Henry’s, an off-campus bar a block from campus. Combined, these two incidents drew national media attention, including from the New York Times.

Helen Nestor

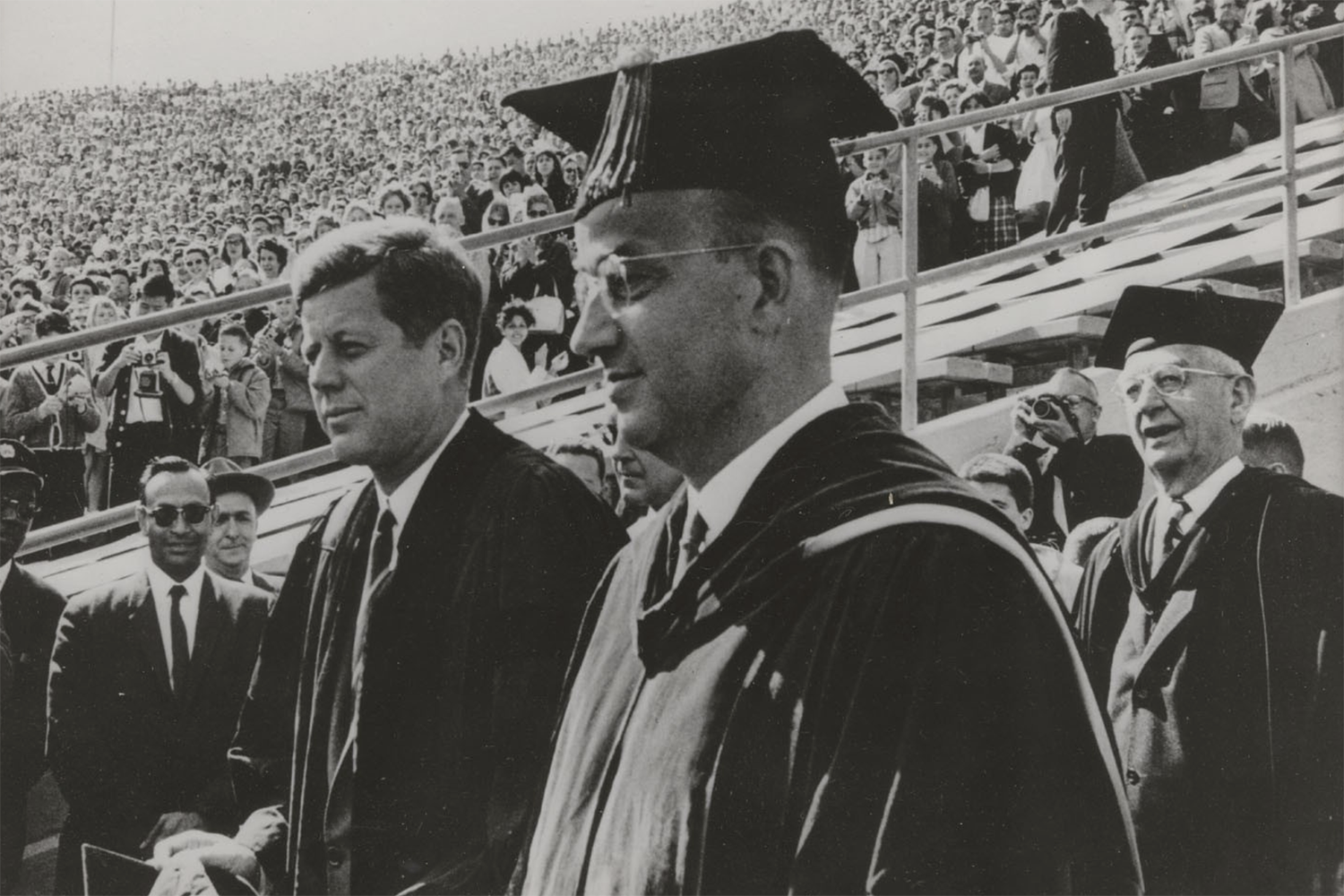

Yet, positive news was regular fare through this long stretch, and Colvig’s career — he began as a Berkeley science writer in 1959 — included four Nobel Prize wins by faculty members; major discoveries in computing, particle physics, photosynthesis and human origins; a 1962 speech in California Memorial Stadium by President John F. Kennedy, who called on Berkeley students to “recognize their responsibilities to the public interest,” and another in 1967 by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., on the Sproul Hall steps, as the Vietnam War raged.

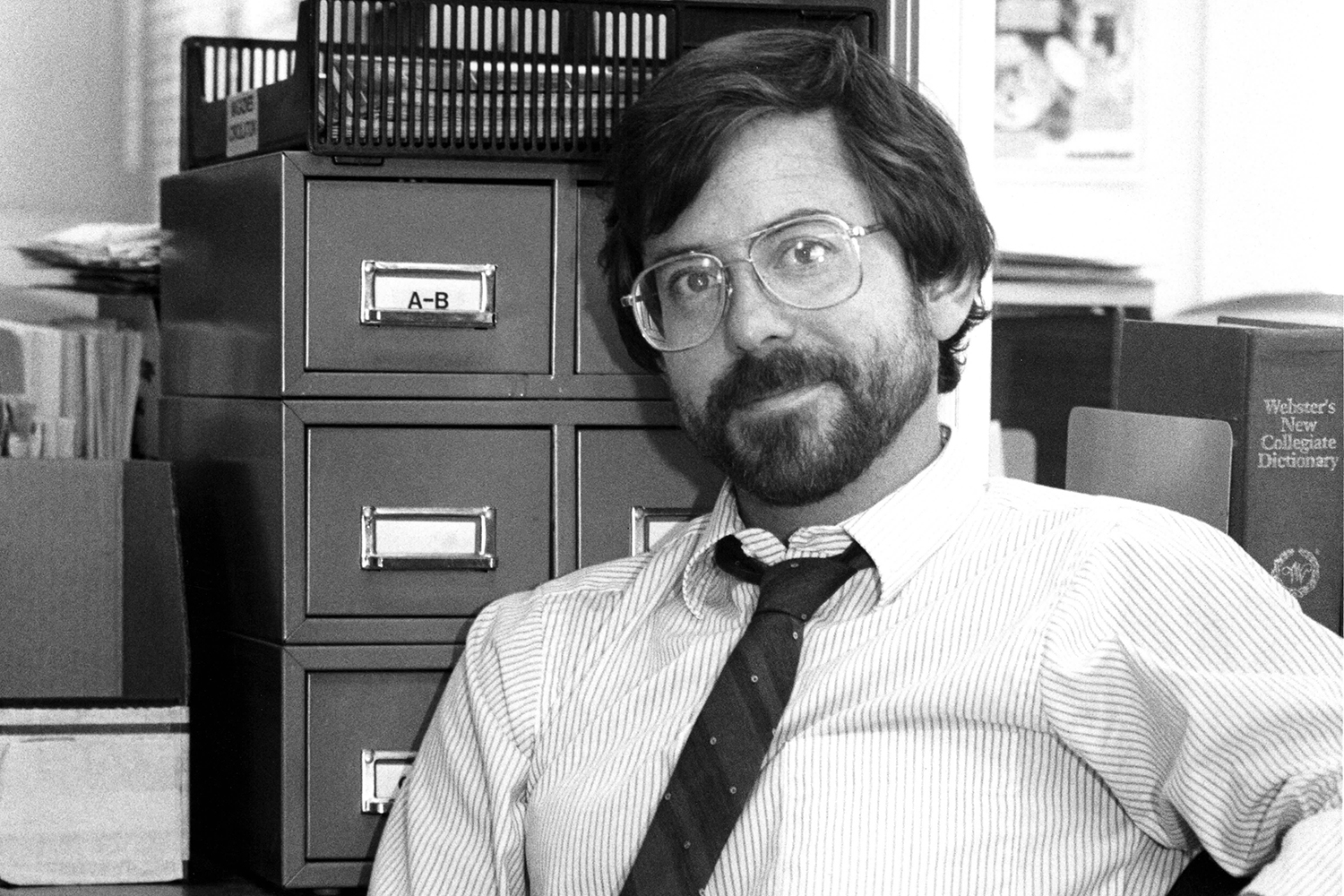

“We’ve had great teams of writers over the years who recognized important campus news and, no matter how scientific, knew how to translate it in a way that reporters got it,” said Robert “Bob” Sanders, the campus’s current manager of science communications who was hired by Colvig in 1991. “And that got UC Berkeley’s name in the news.

“Our researchers and scholars have a well-deserved reputation for excellence, but I like to think that we have played a big part in the public’s recognition of that fact.”

Peg SKorpinski for UC Berkeley

A changing landscape for higher ed and the media

If Ray Colvig handled a seemingly endless stream of difficult news, Sanders has spent 34 years at Berkeley publicizing some of the world’s most important scientific discoveries and innovations, which he says have become so plentiful in the past few decades that “it’s like they’re coming from a firehose.”

The pace of scientific discovery, and the quantity of science news on campus, have risen thanks to research money coming to Berkeley, he said, “and there are developments in every field. And faculty members who used to be loath to talk to the media are now eager, and they want our help.”

Reporting major news that benefits society is a priority for Sanders and his news team colleagues, who cover the campus’s wide array of academic fields, at times in collaboration with communications colleagues in individual Berkeley departments, colleges and schools.

In 2024, Sanders successfully publicized a new process by Berkeley chemists that vaporizes plastic bags and bottles, creating gases that make new, recycled plastics. And recently, he reported a medical first: A baby’s life was saved as a legacy of CRISPR gene-editing technology developed by Jennifer Doudna, a Berkeley professor who won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Robert Sanders/UC Berkeley

The news team’s increasing use of inviting videos, images, social media posts and podcasts amplifies its news releases and online UC Berkeley News stories.

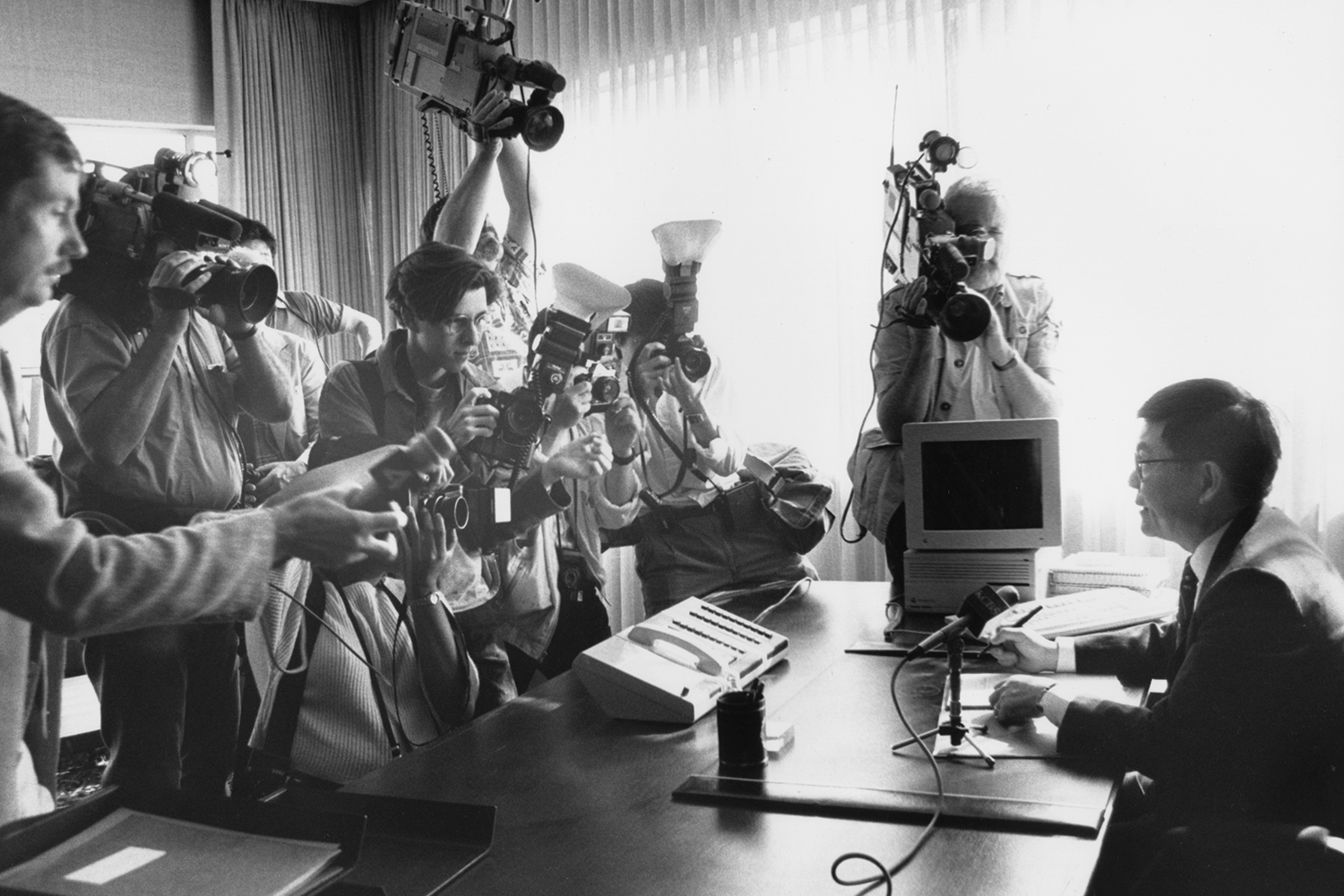

News and Media Relations excels at helping scholars translate their complex research findings into everyday language, coaching them to work effectively with the media, and identifying faculty experts to comment on current events, from climate change to U.S. Supreme Court rulings to A.I. Resulting news coverage, frequently in prominent national and international media outlets, helps position many Berkeley scholars as leaders in their fields. And sometimes, one of them wins a Nobel Prize.

To date, Berkeley has 26 Nobel laureates. Four times in campus history — 1946, 1951, 1959 and 2020 — the news team handled Nobel wins by two faculty members in the same week. It constantly is perfecting its detailed annual plan for the Nobel Prize announcements in early October.

“So many of the great things that have happened here in our labs would be ignored in the local and national press were it not for the efforts of the staff in the Office of Communications and Public Affairs. I have benefitted directly from this,” said Randy Schekman, who won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

As the entire Office of Communications and Public Affairs heads into its 101st year, it faces new hurdles, and opportunities, as the landscape continues to shift for both public higher education and the media.

The state’s contribution to Berkeley’s budget has slowed considerably since 2000, and while it has maintained its excellence, the campus is now closely monitoring federal government plans that could have negative impacts. The media, meanwhile, has seen a decline in newspapers; the advent of the internet, social media and the iPhone; and rising partisan journalism, disinformation and misinformation.

Courtesy of Aileen Zerrudo

In the footsteps of Ellis, Colvig and other Berkeley communications leaders, Aileen Zerrudo began her new post June 1 as associate vice chancellor and chief communications officer. In this climate, the Berkeley alumna said, it’s important to carefully manage Berkeley’s reputation, find new ways to engage with select media, and prioritize storytelling that touts the campus’s unparalleled advances for society.

“For 100 years,” she said, “this department has been a bridge to the world. Harold Ellis understood that our job isn’t just to share news, but to help society understand Berkeley’s distinct impact. Today, we’re building on that foundation by ensuring Berkeley’s contributions to the greater good are clearly understood.

“The next century of our story is just beginning, and the Office of Communications and Public Affairs is committed to telling it with the same excellence and integrity that has defined it since 1925.”