Falcon fans mourn and remember Nox, UC Berkeley’s youngest peregrine

Nox's death on Wednesday is being met with tears and tributes, and with gratitude for the experts who tried to save him.

October 24, 2024

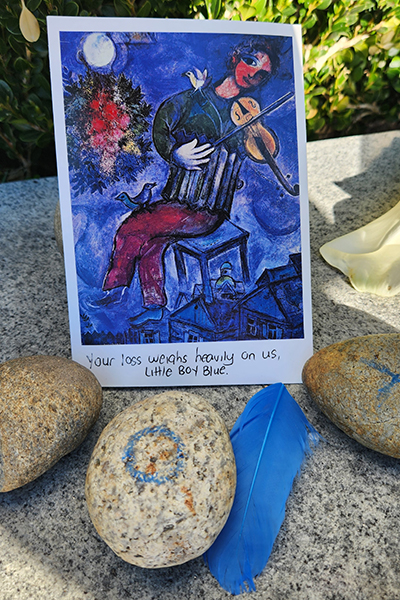

His name was Equinox — a fitting one, since he and his siblings hatched on UC Berkeley’s Campanile during Earth Week last April. But the tiniest of the four peregrine falcon chicks quickly acquired two nicknames: Nox and Little Boy Blue.

As news spreads of his death yesterday (Wednesday, Oct. 23) at UC Davis Veterinary Medical Hospital, tributes like these are pouring in on Cal Falcons’ social media channels: “Little Boy Blue … forever missed.” “Loved that little dude.” “Light a Blue Candle for Nox.”

Courtesy of UC Davis California Raptor Center

Blue tape was placed on May 15 around Nox’s right leg when he received his ID bands, to distinguish him from his brother and two sisters. In Latin, “Nox” means night, and the color blue is often associated with nighttime.

On Monday, the six-month-old falcon was rescued in Richmond from a resident’s yard and taken to UC Davis with acute emaciation. He received a blood transfusion at the veterinary hospital from another falcon, but didn’t survive. The previous week he’d been released into the wild, following surgery at the hospital in July for an injury and months of rehabilitation.

Sean Peterson, an environmental ecologist with Cal Falcons, said his group is “completely devastated. … Losing him is incredibly difficult, especially with how much work he and his human caretakers put in to return to the wild from his initial injury.”

Nox suffered a broken wing on July 3 in the Berkeley Marina. After a successful surgery at UC Davis’ veterinary hospital, he recovered at the UC Davis California Raptor Center and then spent a month with a falconer, who painstakingly trained him for life on his own.

Then, on Oct. 18, many of those who helped him heal watched him fly away, looking strong, after his release at an East Bay shoreline park.

Bridget Ahern for UC Berkeley

“We’re all grieving right now,” said Michelle Hawkins, the center’s director, who was at the event. “And we want to send our condolences to Cal Falcons.

“Wildlife can really break your heart, because even with the best knowledge, the best medicine, they sometimes don’t make it. Everyone who cared for this little bird formed ties with him. They felt that same pull and magnetism that you feel when you’re around a peregrine.”

Hawkins said extensive tests will be conducted at UC Davis to try and determine the cause of death, and that it could take a month or more for the results.

Berkeley’s falcon family drama continues

Berkeley’s falcons have experienced considerable drama in recent years. In October 2021, Grinnell, longtime mate to Annie — the mother of 22 chicks since her arrival on campus in 2016 — was attacked by rival falcons. A month later, after weeks of rehabilitation, he was set free and returned to campus. But on March 31, 2022, Grinnell was found dead in downtown Berkeley.

Bridget Ahern for UC Berkeley

Annie then had three mates in succession — Alden and Lou, who both disappeared, and now Archie, father to the spring siblings. The pair has had to fend off intruding falcons, and drones have flown illegally and too close to their nest. Three of Annie’s young have died over time — Lux, Lindsay and now Nox. A fourth, Sequoia, is thought to have succumbed to bird flu in San Jose.

A welcome turn of events took place last April, when all four of Annie’s eggs hatched — a spectacle celebrated by a large crowd that saw the new chicks in a live webcast on the large outdoor screen of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

“Annie had never successfully hatched all four eggs in any year we’ve monitored her,” said Peterson. “There was always an egg or two that didn’t make it.

“Nox was the exception to that: a tiny little bundle of fluff that hatched out of his egg as hundreds of people watched live on BAMPFA’s big screen.”

Grief, and joy in remembering

Upon hearing of Nox’s death, wildlife photographer Bridget Ahern said she “immediately burst into tears. Hard crying.” She’s chronicled the Berkeley falcons’ lives since 2020, including the chicks’ first flights each year.

Bridget Ahern for UC Berkeley

“Nox was just such a tiny little sprite, but he definitely had a personality and was loud,” she recalled.

When Nox started flying in June, she said, “he didn’t have the best landings to begin with, and tried to land in places where it wasn’t exactly possible. But he was one of the first to get prey from Annie and got fairly agile.”

“People just adored him,” added Ahern. “They’d literally come to campus and ask me, ‘How’s Nox doing?’ from the perspective of fandom, not concern. He was just a little squirt; people were just drawn to him.”

Peterson watched Nox grow up via the bell tower’s three 24/7 webcams, one of them focused solely on the nest. He said Nox “had an immediately captivating joy and energy whenever he was on camera.”

Nox’s uniqueness was his small size and his adventurousness, added Mary Malec, a longtime member of Cal Falcons.

Bridget Ahern for UC Berkeley

“He was the most adventurous of them all,” she said. “He even flew through the bars of the Campanile’s observation deck on his second day (flying). He had a speed and an eagerness to just be out there.”

Knowing Nox is gone, said Malec, makes her feel “worse than when I heard that Grinnell died. This is harder for me. Grinnell had a full life. He’d already had 12 kids. Nox had a month and three and a half days of freedom.”

Nox flew free for a month after fledging off the tower, before breaking a wing. He got to experience flying dozens of miles — to Treasure Island and San Pablo Bay and places in between — for three days after his Oct. 19 release.

His life was too short, said Peterson, but “we will all always treasure the moments we had with him.”